Steps towards religious tolerance – Prague

Czech figure of the „Religious tolerance and intolerance” topic

Freedom of religion and religious tolerance belong to the fundamental values of a democratic society. Such principles are connected with respect for the plurality of opinions and social tolerance, in the Middle Ages and well into the early modern era, however, freedom of conscience was not held in such high regard. Tolerance used to be imposed by the necessity of coexistence of religiously, linguistically and ethnically heterogeneous groups of the populace. Later on, by the 18th century, tolerance increasingly related to the prioritisation of state interests over particular ecclesiastical structures. Nonetheless, several noticeable milestones of tolerance may be identified in Czech history, that is periods when differing religious groups were willing to discuss peacefully and reach mutual compromise.

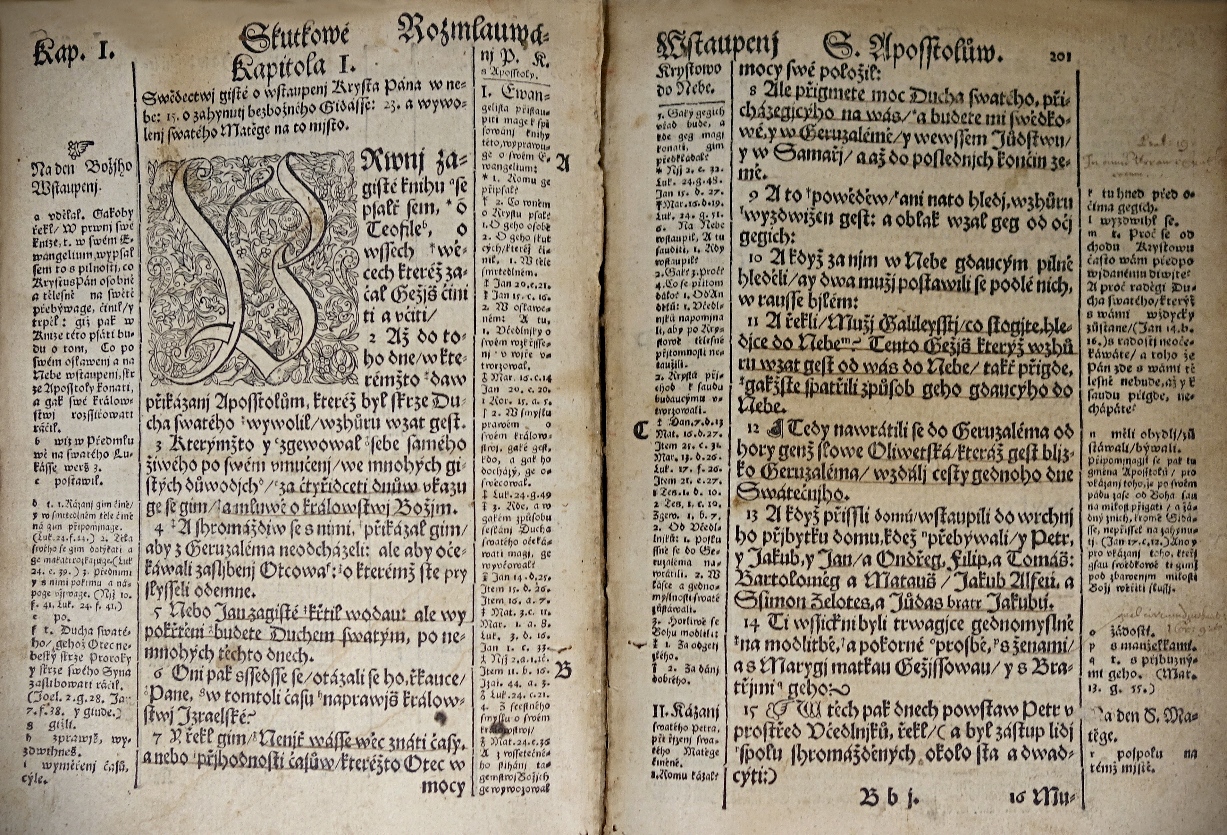

A distinct feature of Czech religious history is, without a doubt, the Hussite movement. Its chief demand was the reception of the communion under both kinds by the laypeople. The movement’s eschatological delirium and its challenge to the authority of both pope and the monarch would classify the Hussites among late medieval sects. However, the repeated failure of anti-Hussite crusades led the representatives of the Roman Church to negotiate with them. For nearly two centuries thereafter, the Hussites constituted a religious group that was at times more, and at other times less, tolerated. The Religious Peace of Kutná Hora in 1485 even declared the one’s freedom to receive communion in both kinds.

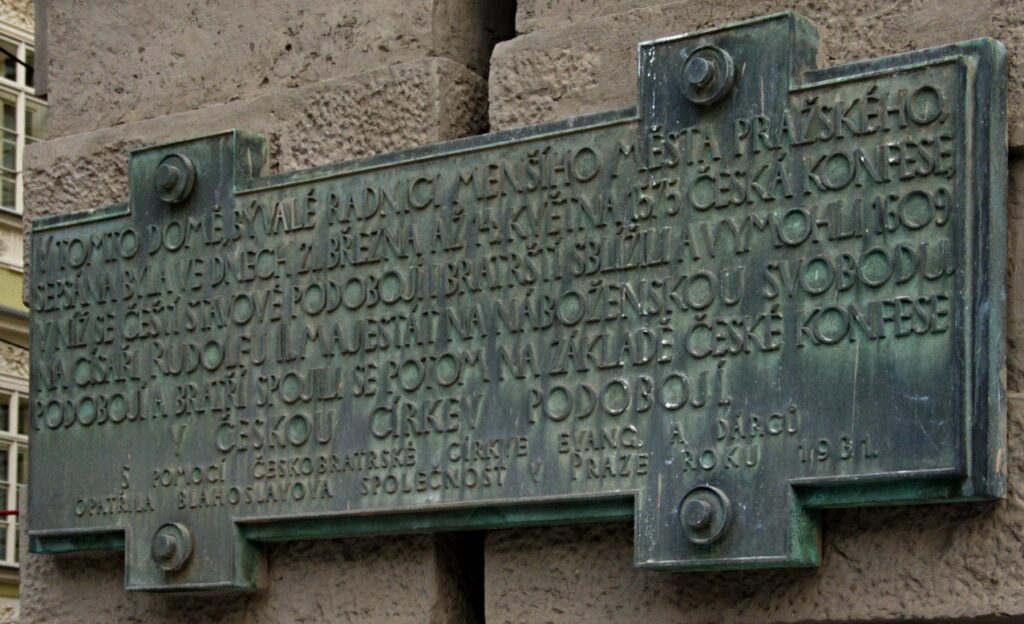

For this reason, after the onset of the Reformation, the Czech lands became an area of exceptional religious diversity. Lutheranism was swiftly adopted, particularly by the German-speaking inhabitants of the cities, who had been staunchly Catholic, and some former Hussites sympathized with it as well. The Unity of the brethren, an independent radically evangelical church that arose from local Hussite traditions, also gained considerable influence in the region. The more conservative faction of the Hussites, on the other hand, began to move closer to Catholicism, which had never disappeared from the country and, in fact, enjoyed direct support from the royal power. Religious matters were largely under the control of the nobility on their own estates, which meant that regions like Moravia became havens for various persecuted sects. Attempts were made to codify freedom of religion as a national law in the Czech Confession of 1575 and Emperor Rudolf’s Majesty of 1609.

However, this period was also marked by sharp confessional disputes, and the failed Bohemian Revolt ushered in an era of uncompromising re-Catholicization. It was not until the 1780s that the Enlightenment state introduced tolerance for selected confessions, albeit from very different motivations. Full equality of churches, not only in private but also in the public sphere, was achieved only in 1861. Legal recognition of a non-religious status followed in 1868.

Facts