In the times when Central Europe found itself on the communist side of the Iron Curtain, culture and its means of expression remained one of the few effective tools of resistance. Both poetry and drama, and later even cinematography, were harnessed in the fight against the oppression of the communist system, expressed not only in the lack of democratic forms of public life but also in a matter that was particularly crucial from the perspective of the intellectual elites—censorship. The criticism took both literal and metaphorical forms.

Resistance rooted in the sphere of culture follows its own rules. Its tools are not stones or Molotov cocktails, just as it is usually not combated with rifles or police batons. Cultural resistance wields the weapons of allusion, suggestion, and irony. This weapon strikes not at the buildings of the police or the party, but at the monuments of ideology and consciousness that the authorities erect in the minds of citizens through education and propaganda. Each decade of the communist era had its own specificity in the relationship between the authorities and society, in which the intellectuals were forced to employ different sets of symbols and make use of different mediums for content.

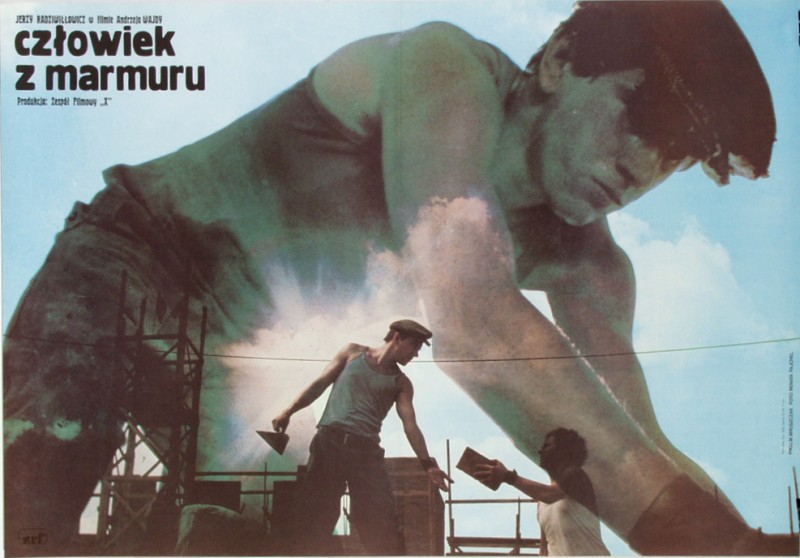

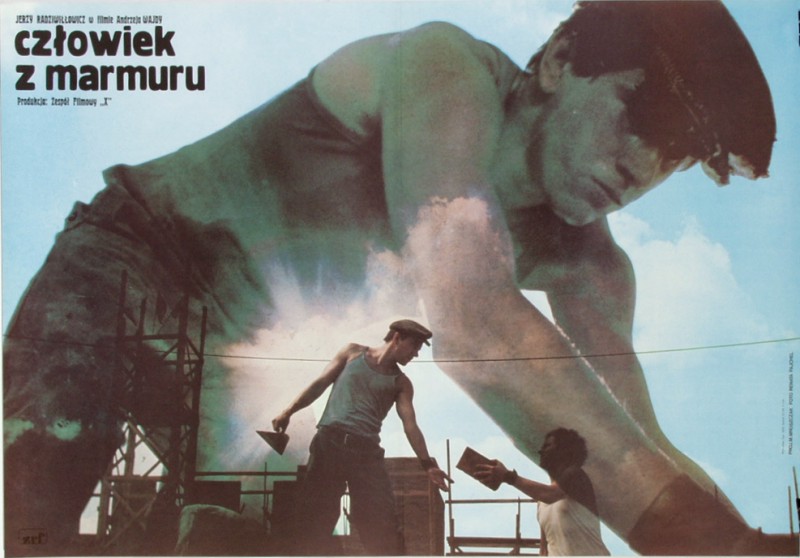

For instance, during the martial law period, the opposition’s artistic circles targeted General Wojciech Jaruzelski, specifically his „Ślepowron” coat of arms and his habit of wearing dark glasses. This, however, was already the art of a period of direct confrontation, when it became clear, as Kaczmarski’s words suggest, that „this one is with us, that one is against us.” The subtle dissent of the intellectual elites against the oppression and deceit of the system was most visible in the 1960s and 1970s. The best example of this is Andrzej Wajda’s film Man of Marble. The film is based on one of the fundamental principles of the „cinema of moral concern”—the deconstruction of myth.

One of the iconic figures of the Stalinist era, the model worker, is depicted as an immature person (almost a child in mental terms), exploited by the system to build an ideological monument. The entire action of the film, focused on the making of a biographical film about the model worker Birkut, step by step reveals the brutality and hypocrisy of the system. The overall impact of the film brings a sense of moral unease into the utopian image of the People’s Republic of Poland and socialism as crafted by its propaganda.

Stephen, the King rock opera – National emotions in communism – Budapest, City Park

The rock opera Stephen, the King (István, a király) stands as a cornerstone of Hungarian cultural heritage, blending history, music, and national sentiment. Composed by Levente Szörényi with lyrics by János Bródy, the opera was based on Miklós Boldizsár’s drama Ezredforduló (Turn of the Millennium). Premiering on August 18, 1983, on the newly named Királydomb (King’s Hill) in Budapest’s City Park, this outdoor performance became an immediate sensation, combining profound storytelling with vibrant musical compositions. Lorenz Klotz’s evocative set design and the cinematic adaptation further elevated the production to legendary status.

Man of Marble (1977) – Nowa Huta

„Man of Marble” by Andrzej Wajda from 1977 is a film about reckoning with the period of Stalinism in Poland. It tells the story of Mateusz Birkut, the forerunner of the work, whose fate is investigated by the young director Agnieszka. Through her investigation, scenes of propaganda, manipulation and the fate of individuals in the machine of power are discovered. The film was made in the difficult realities of the Polish Republic, as a bold critique of the system, which was met with censorship and delay of the release. „Man of Marble” became a symbol of artistic and political courage.

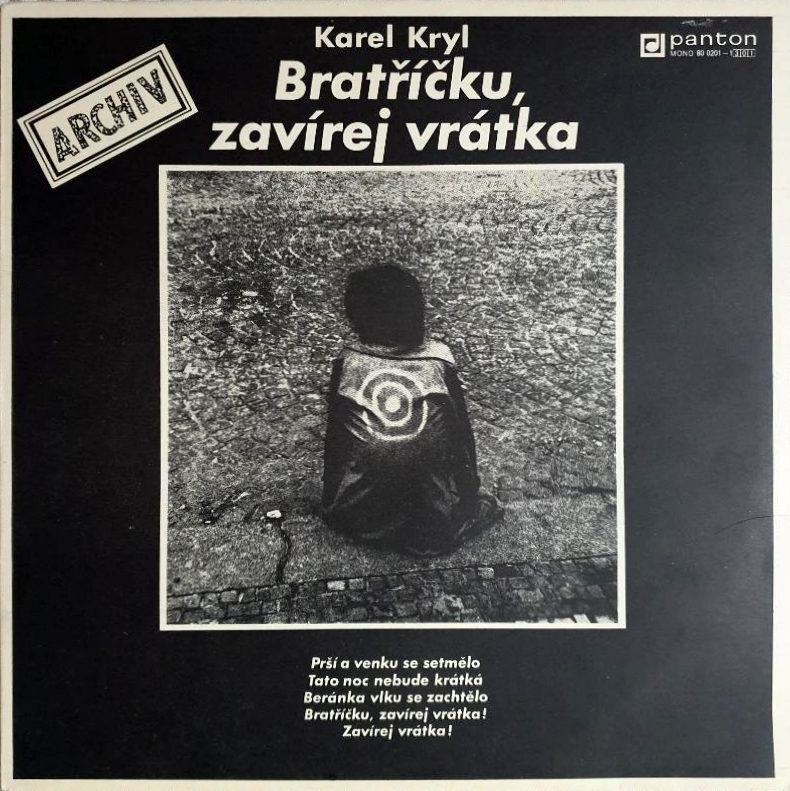

The independent culture under the communist regime – Ostrava

Culture is an important part of every community. In socialist Czechoslovakia, culture played an essential role both for the communists and for groups that were politically and ideologically on the other side. The television entertainment was the main way in which the communist party maintained its legitimacy, but culture in general was equally important to those who disagreed with political situation or sought something other than state-controlled cultural offerings. In the Eastern Bloc, culture often became an expression of disapproval of the communist government.