Myth of Kossuth – Vidin

Fact of the Hungarian figure „Hungarian independence from the Habsburg dynasty„

Part of the „Revolutions of 1848″ topic

Lajos Kossuth, a central figure in Hungarian history, became a symbol of freedom and independence during and after the 1848–49 Revolution. Following the Hungarian defeat at Világos, Kossuth fled to Vidin, in the Ottoman Empire, marking the beginning of his long exile. Vidin serves as a symbolic location, not only for Kossuth’s retreat but also for his contentious act of branding Artúr Görgei a traitor in the infamous Vidin Letter, a decision that shaped both Hungarian memory and the dynamics of the nation’s revolutionary legacy.

Kossuth’s letter accused Görgei of betraying Hungary by surrendering to the Russian forces, a pragmatic decision Görgei made to avoid further bloodshed. The accusation divided Hungarian opinion for decades, casting Görgei as a scapegoat while elevating Kossuth as the uncompromising hero of independence. This narrative deeply influenced Hungarian memory, embedding Kossuth as a martyr and symbol of resistance, despite his decision to flee and leave others to face retribution.

In exile, Kossuth became a global advocate for Hungary’s independence. He toured extensively, most notably in the United States and Great Britain, where he was celebrated as a champion of liberty. In America, his speeches resonated with the ideals of freedom and democracy, earning him widespread admiration. He also garnered support from Hungarian diaspora communities, reinforcing his role as the voice of the Hungarian cause abroad. Kossuth’s exile, however, was marked by personal sacrifices and a growing realization of the limitations of his influence in altering Hungary’s fate under Habsburg rule. During his thirty years in exile, Lajos Kossuth lived in several countries, including Turkey (Vidin, Kütahya), the United States, and Italy (Turin), where he spent the final years of his life.

The funeral of Lajos Kossuth on April 1, 1894, in Budapest, marked one of the most significant moments of Hungarian national remembrance during the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, with Emperor Franz Joseph still on the throne. Kossuth, a towering figure in Hungarian history, had passed away on March 20, 1894, after a long illness. His death reverberated across Hungary, symbolizing the end of an era for a man synonymous with liberalism, national independence, and the ideals of the 1848 Revolution.

Kossuth’s death at the age of 92 was followed by an outpouring of grief. The Hungarian Parliament and national leaders, including Prime Minister Sándor Wekerle and figures like Albert Apponyi, paid their respects. However, the Austrian territories remained indifferent, reflecting the political tensions between Hungary and Vienna. Once Kossuth’s remains crossed into Hungary at Csáktornya, mourners gathered in thousands, singing the Kossuth Song and giving speeches at every stop along the train’s journey to Budapest.

Upon arrival at the Nyugati Railway Station, Kossuth’s coffin was received by a massive crowd and brought to the Hungarian National Museum, where his body lay in state. On the day of the funeral, delegations from across the country and nearly half a million people attended. Despite its immense national significance, the funeral was intentionally devoid of official state and military representation due to Franz Joseph’s directive. Even prominent government officials like Bánffy Dezső, the President of the House, abstained from attending officially.

Kossuth’s legacy persisted through subsequent regimes. During the communist era in Hungary, his image was co-opted as part of the official narrative, reframed as a symbol of revolutionary struggle and anti-imperialist resistance. The communists highlighted his defiance of the Habsburgs while downplaying his liberal ideals and transatlantic advocacy for democracy. This selective appropriation underscored his enduring status as a malleable figure in Hungarian political memory, adaptable to diverse ideological contexts.

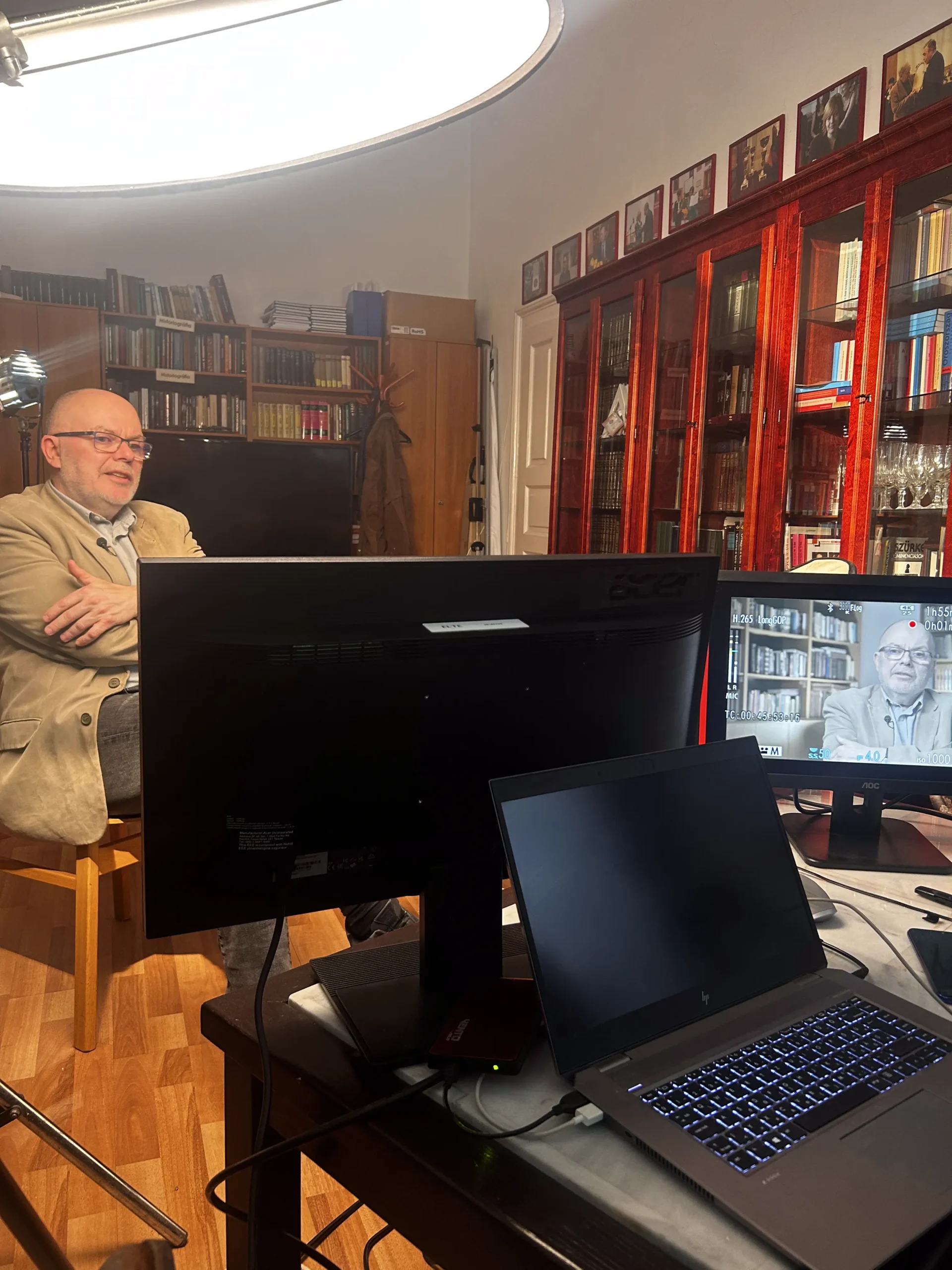

Filming Begins for the ReCall Microcourse: Unity and Diversity – Central Europe Through The Centuries (April 2025)

Filming Begins for the ReCall Microcourse: Unity and Diversity – Central Europe Through The Centuries (April 2025)