Capitulation and collapse – Világos

Fact of the Hungarian figure „Hungarian independence from the Habsburg dynasty„

Part of the „Revolutions of 1848″ topic

The capitulation at Világos on August 13, 1849, marked the tragic end of the Hungarian War of Independence, a moment that symbolized both defeat and resilience in Hungarian history. The surrender occurred in the shadow of overwhelming odds as the combined forces of the Austrian and Russian empires vastly outnumbered the Hungarian forces. The intervention of Tsar Nicholas I, responding to Austria’s plea for assistance, brought a colossal Russian army into Hungary, tipping the scales irreversibly against the Hungarian troops.

The Russian forces that intervened in the Hungarian War of Independence were led by Field Marshal Ivan Fyodorovich Paskevich, a seasoned and highly regarded military commander in the Russian Empire. Paskevich had earned his reputation in earlier campaigns, including the Russo-Turkish Wars and the Polish November Uprising of 1830-31, where his decisive leadership contributed to the crushing of Polish resistance. By 1849, he was a trusted figure of Tsar Nicholas I, tasked with ensuring that revolutionary movements in Central Europe did not destabilize the established monarchical order. His appointment underscored the seriousness with which the Russian Empire regarded the Hungarian conflict, as Paskevich was seen as the most capable general to lead such a critical intervention.

Paskevich commanded a massive force, numbering around 200,000 soldiers, a stark contrast to the increasingly stretched Hungarian army. Despite his overwhelming superiority in manpower and resources, Paskevich faced significant challenges, including difficult terrain, disease among his troops, and the tenacity of Hungarian resistance. Nevertheless, his calculated and methodical approach eventually overwhelmed the Hungarian forces. His involvement culminated in the siege of Világos, where Hungarian General Görgei laid down arms to the Russians rather than face further bloodshed. Paskevich’s victory cemented his legacy as a formidable military leader, though it also symbolized the crushing of Hungarian aspirations for independence—a reality that would linger in Hungarian memory for generations.

Despite the dire circumstances, Hungarian commanders like Józef Bem and György Klapka demonstrated extraordinary valor. Bem’s campaigns in Transylvania were legendary for their ingenuity and tenacity, while Klapka’s defense of Komárom held out long after Világos, serving as a beacon of defiance. Their efforts kept the spirit of resistance alive even as defeat loomed inevitable.

General Artúr Görgei, often unfairly maligned for his role, made the rational decision to surrender to the Russians at Világos rather than face the Austrians. This act, while controversial, aimed to minimize unnecessary loss of life among Hungarian troops. Görgei’s pragmatism was later vindicated by history, yet he bore the brunt of public outrage for decades, branded as a scapegoat for the failure.

The aftermath of Világos was devastating. The Habsburgs enforced harsh reprisals, including the infamous execution of the 13 Martyrs of Arad, but the resilience of the Hungarian spirit endured. The mythos of the Hungarian honvéd (soldier) emerged, turning surviving veterans into symbols of national pride. In the late 19th century, Honvéd Associations formed across Hungary, fostering camaraderie and honoring their service. These organizations held a vital role in preserving the memory of the independence struggle, with aging veterans celebrated as national heroes, often referred to as „living relics” of Hungary’s fight for freedom.

The last Hungarian freedom fighters of 1848-49 hold a special place in the nation’s collective memory, symbolizing a bygone era of valor and sacrifice. By the 1920s, the number of surviving veterans had dwindled dramatically, their average age exceeding 90 years. Despite their declining health, these figures remained highly revered, often invited to state ceremonies, monument unveilings, and national celebrations. Their presence served as a poignant reminder of Hungary’s struggle for independence.

Among the veterans, István Lebó became the symbolic „last soldier of 1848,” partly due to his residence in Budapest’s Honvédmenház (Veterans’ Home). His death on June 1, 1928, was marked by a grand national funeral, including a public procession from the National Museum to the Fiumei Road Cemetery, where he was buried with full military honors. The event drew tens of thousands, affirming the public’s enduring respect for these historical figures.

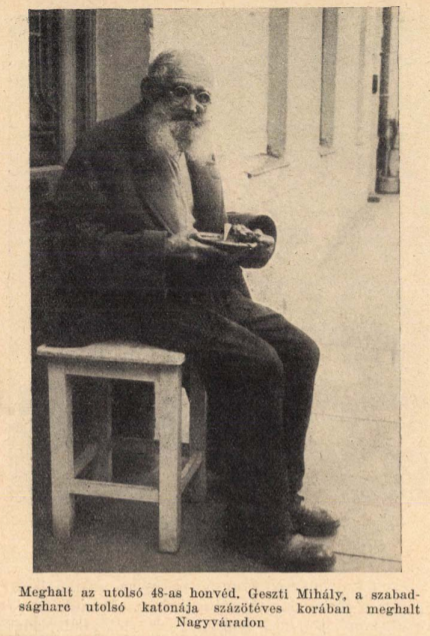

However, records reveal that other veterans, such as Jakab Khun and Mihály Geszti, outlived Lebó but did not receive the same recognition. Factors such as health, geographic isolation, and even religion sometimes excluded them from the national narrative. For instance, Khun, an orthodox Jew, was denied a state funeral due to his family’s wishes for a private burial. Similarly, Geszti, a resident of Nagyvárad (now Oradea, Romania), remained outside Hungary’s post-Trianon borders, limiting his visibility in official commemorations.