József Eötvös’s Nationality Law and the violent attempts at Magyarization – Budapest, Eötvös-Monument

Fact of the Hungarian figure „No. No. Never.” – Treaty of Trianon”

Part of the „The myth of national disaster” topic

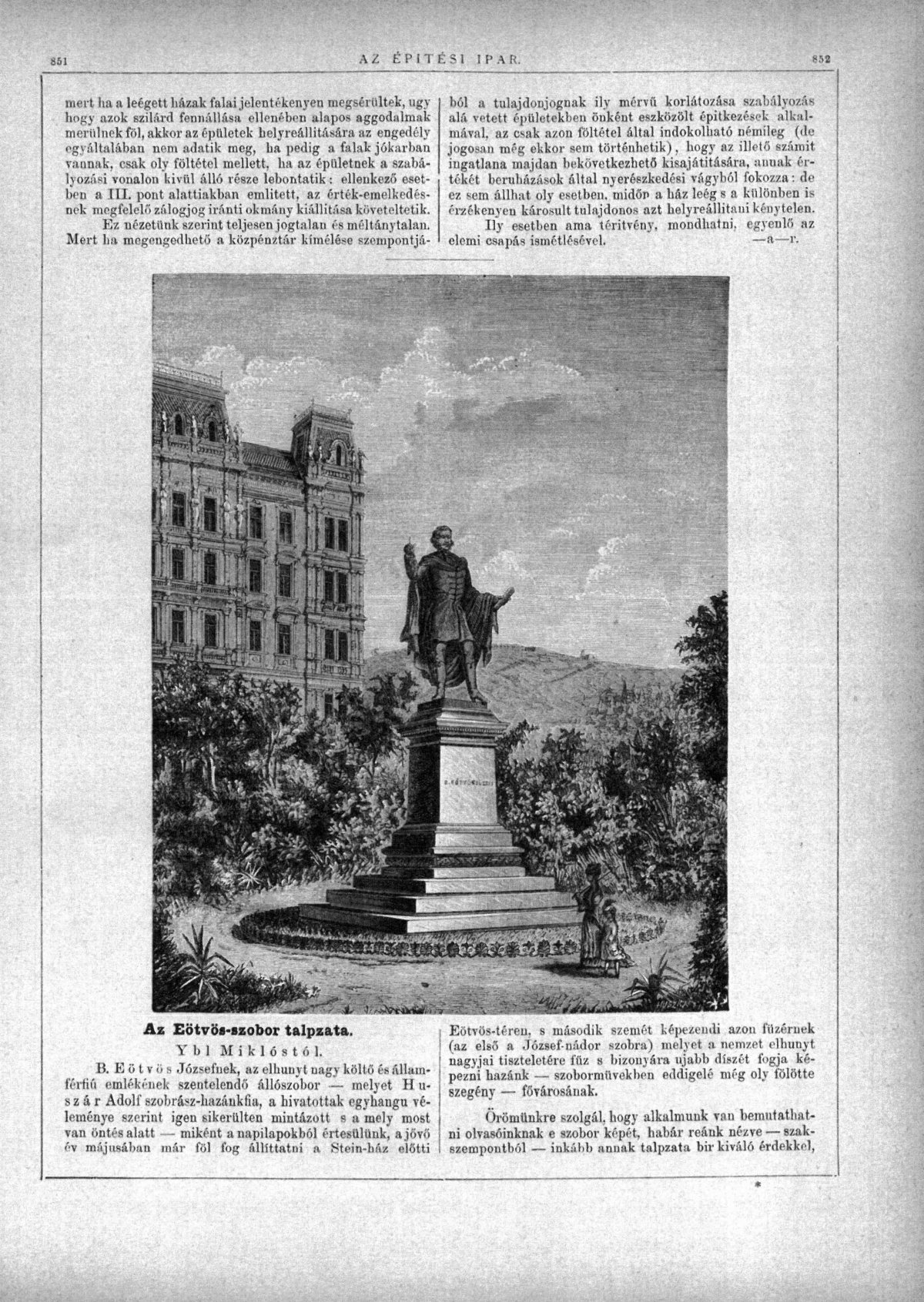

The Eötvös Monument in Budapest honors Baron József Eötvös, a key figure in Hungarian political and intellectual history, recognized for his progressive views on nationality and education. Eötvös, a statesman and writer, played a crucial role in drafting Hungary’s Nationality Law of 1868, which aimed to address the complex ethnic composition of the Hungarian Kingdom within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The law sought to provide cultural autonomy and rights to the various nationalities within Hungary, promoting equality and the peaceful coexistence of different ethnic groups.

However, despite Eötvös’s intentions, the implementation of the law was often overshadowed by the rise of Magyarization—a policy aimed at assimilating non-Hungarian nationalities into Hungarian culture and language. These efforts led to significant tensions and resistance among Hungary’s ethnic minorities, including Slovaks, Romanians, Serbs, and others.

The consequences of these policies were far-reaching, contributing to the deep-seated national grievances that would later be exacerbated by the Treaty of Trianon in 1920. The treaty, which followed the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire after World War I, drastically redrew Hungary’s borders, resulting in the loss of two-thirds of its territory and millions of ethnic Hungarians finding themselves in newly formed states. This redrawing of borders created enduring ethnic and political tensions in Central Europe, where the legacy of Magyarization continued to influence interethnic relations.

Eötvös’s Nationality Law, while progressive in its intent, ultimately could not prevent the rise of nationalist conflicts that shaped the region’s history. The monument to Eötvös in Budapest serves as a reminder of the complexities of managing ethnic diversity in a multi-national state and the challenges of fostering genuine equality among different nationalities. In the broader context of Central European history, his efforts highlight the ongoing struggle to balance national identity with the rights of ethnic minorities. This struggle remains relevant in the region’s post-World War I landscape.