Hungarian revisionist memory between the two world wars – Hungarian Calvary, the 100th National Flag Monument

Fact of the Hungarian figure „No. No. Never.” – Treaty of Trianon”

Part of the „The myth of national disaster” topic

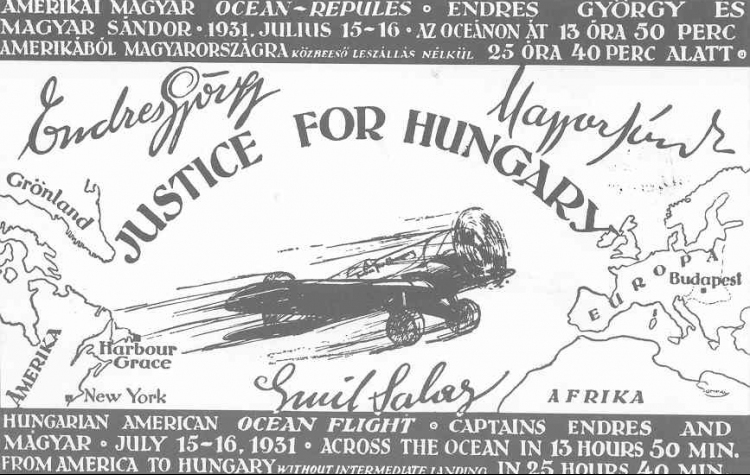

Hungarian Revisionist Memory

Sátoraljaújhely, a town in northeastern Hungary, became a significant symbol of Hungarian revisionist memory during the interwar period. The Kálvária (Calvary) Hill in Sátoraljaújhely, with its religious and historical connotations, became intertwined with Hungary’s national trauma following the Treaty of Trianon in 1920. The Trianon Treaty left a deep scar on the Hungarian national consciousness, giving rise to a powerful revisionist movement that sought to reverse the territorial losses. The phrase „No, No, Never” became the rallying cry of this movement, expressing the nation’s refusal to accept the new borders imposed by Trianon. The Kálvária Hill in Sátoraljaújhely was transformed into a memorial site, where nationalistic and revisionist sentiments were expressed through religious and patriotic ceremonies. These gatherings often included prayers for the lost territories and calls for their return to Hungary.

During the interwar period, Sátoraljaújhely and other similar sites across Hungary played a crucial role in sustaining the revisionist agenda. This movement was not only a domestic political force but also influenced Hungary’s foreign policy as the country sought alliances and opportunities to revise the Treaty of Trianon. The revisionist sentiment, however, contributed to tensions with Hungary’s neighbors, particularly those that had gained territory as a result of Trianon, such as Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia.

The memory politics of the interwar period, exemplified by the Kálvária in Sátoraljaújhely, highlight the complexities of Central European relations in the aftermath of World War I. Hungary’s desire for territorial revision sharply contrasted with its neighbors’ efforts to consolidate their new borders and national identities. These conflicting aspirations created a volatile environment in Central Europe, ultimately contributing to the region’s instability leading up to World War II.

Sátoraljaújhely’s Kálvária is a potent symbol of Hungarian revisionism and the enduring impact of the Treaty of Trianon on Hungary’s national identity. It serves as a reminder of the deep historical grievances that shaped Central European politics in the 20th century and continue to influence the region’s interethnic and international relations today.