Serbian–Hungarian Baranya–Baja Republic – Pécs

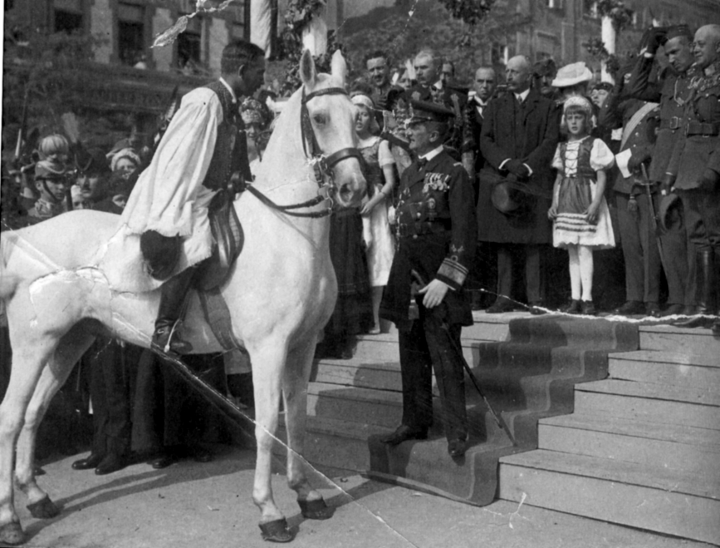

Fact of the Hungarian figure „Arrival of Horthy”

Part of the „Creation of the modern states (1918-1920)” topic

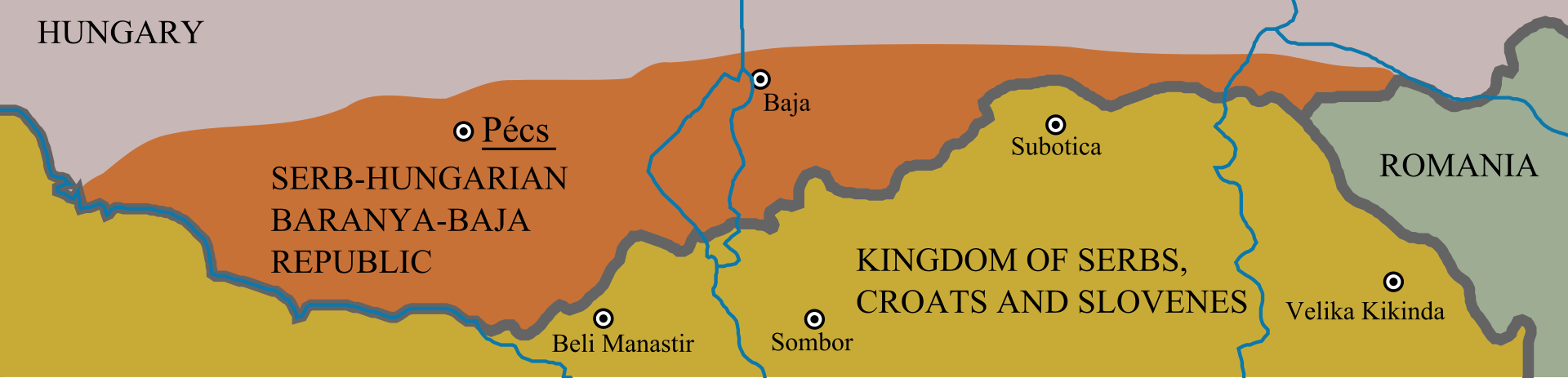

The Serbian–Hungarian Baranya–Baja Republic was a short-lived puppet state proclaimed on 14 August 1921 in Pécs, in the territory occupied by the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. This region, despite being assigned to Hungary by the Treaty of Trianon, remained under Serbian military occupation following the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The „republic” covered a narrow strip of southern Hungary, and its establishment was driven by local communist politicians who sought to oppose the counter-revolutionary Horthy regime.

The Baranya–Baja Republic aimed to create a socialist government and viewed the Horthy regime, which was consolidating power in Budapest, as a threat to their revolutionary goals. The leaders of the republic negotiated with Belgrade to maintain Serbian military presence, hoping it would provide enough protection for their fledgling government. However, the „republic” never gained legitimacy. Neither the Hungarian government in Budapest nor the representatives of the Entente powers recognized its existence, leaving it reliant solely on the occupying Serbian forces for survival.

The republic’s fragile existence ended after just eight days. On 21 August 1921, the first squadron of Hungarian gendarmeries arrived in Pécs, followed by the National Army troops the next day. This marked the end of 33 months of Serbian occupation in southern Hungary and the dissolution of the Baranya–Baja Republic. Pécs and the surrounding areas returned to Hungarian control, and the brief attempt to establish a communist stronghold in the region was swiftly crushed by Horthy’s forces.

The events in Pécs and the short existence of the Baranya–Baja Republic are emblematic of the broader political instability that plagued Central Europe in the aftermath of World War I The dissolution of the Baranya–Baja Republic, followed by Horthy’s arrival and the reassertion of Hungarian authority, mirrored these larger regional dynamics, where conservative and nationalist forces ultimately prevailed over communist movements. Horthy’s successful reclamation of Pécs signaled his growing dominance in Hungary, further consolidating his authority after the fall of the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919.