Semmelweis – Saviour of mothers – Semmelweis Museum, Budapest

Hungarian figure of the „Pandemics” topic

The Semmelweis Museum in Budapest pays tribute to one of Hungary’s most renowned medical figures, Ignác Semmelweis, who is widely regarded as the „Saviour of Mothers.” Born in 1818 in Buda, Semmelweis made groundbreaking discoveries in the field of medical hygiene, particularly in reducing maternal mortality due to puerperal fever. His work revolutionized obstetric practices in Europe and beyond, making a profound impact on the field of medicine and public health.

Semmelweis’s discovery came while working at the Vienna General Hospital in the 1840s. He observed that women who gave birth in the hospital’s First Obstetrical Clinic, where medical students assisted in deliveries, had a much higher mortality rate than those in the Second Clinic, which was staffed by midwives. Through meticulous observation, Semmelweis concluded that the cause of puerperal fever was the transfer of infectious materials by the hands of doctors who moved from autopsies to childbirth without washing their hands. He introduced the practice of handwashing with a chlorine solution, which dramatically reduced mortality rates. Despite the overwhelming success of this simple yet revolutionary practice, Semmelweis faced intense resistance from the medical community, which did not readily accept his ideas during his lifetime.

The Semmelweis Museum, located in his birthplace in Budapest, preserves his legacy, showcasing his life and work through exhibitions and educational programs. His discoveries remain a cornerstone in the history of epidemiology and public health. Semmelweis’s contribution transcends Hungarian borders, influencing medical practices across Europe. In the broader context of pandemics and public health crises, his emphasis on hygiene and infection control resonates strongly, particularly in times like the COVID-19 pandemic, when hand hygiene once again became a crucial public health measure.

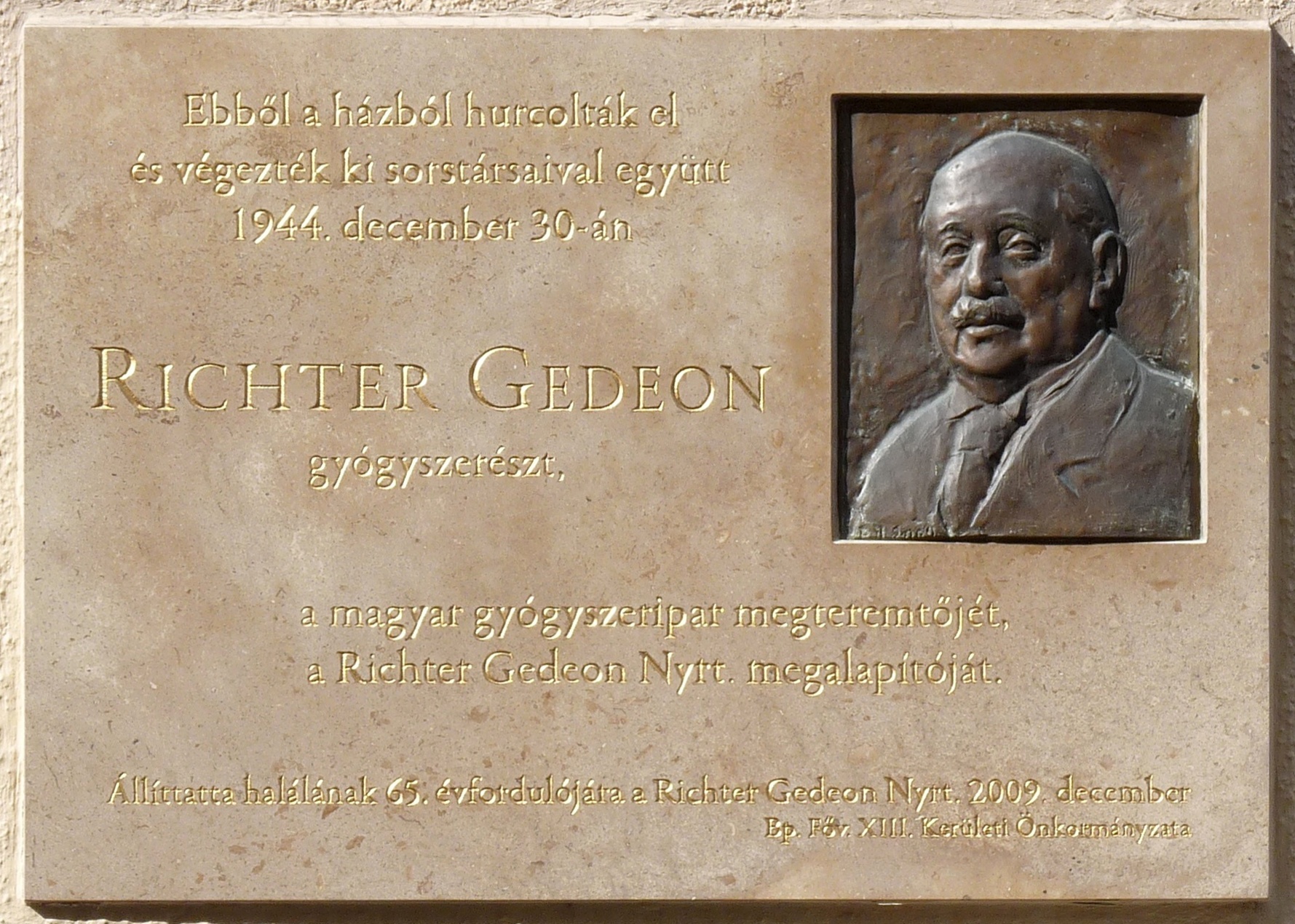

Hungary’s medical heritage extends beyond Semmelweis. The Szent Rókus Hospital in Budapest, home to Europe’s first central X-ray laboratory in 1898, marked another critical step in medical innovation, contributing to diagnostic advancements. The development of the Hungarian pharmaceutical industry also owes much to figures like Gedeon Richter, who founded Hungary’s first pharmaceutical factory in the early 20th century. His contributions laid the groundwork for the country’s robust pharmaceutical sector, which remains a significant player in Central Europe.

Throughout Hungarian history, public health challenges like the plague and cholera have shaped the country’s medical response. The Statue of the Holy Trinity in Buda Castle stands as a reminder of the devastating plague epidemics that swept through Hungary in the 18th century, while the peasant uprising in Eperjesenyicke, Slovakia, in 1831, due to the cholera epidemic, reflects the social unrest these pandemics often triggered.

In more recent times, Hungary has produced modern pioneers in epidemiology, such as Katalin Karikó, whose work on mRNA technology became instrumental in developing the COVID-19 vaccines. Her groundbreaking contributions highlight Hungary’s ongoing role in the global fight against pandemics and underline the nation’s legacy in advancing medical science.

Central Europe’s history of medical innovation and public health responses offers valuable lessons for current and future pandemics. Figures like Semmelweis, Richter, and Karikó exemplify how individual contributions can change the course of medical history, from handwashing practices in the 19th century to cutting-edge vaccine technology in the 21st century.

Facts