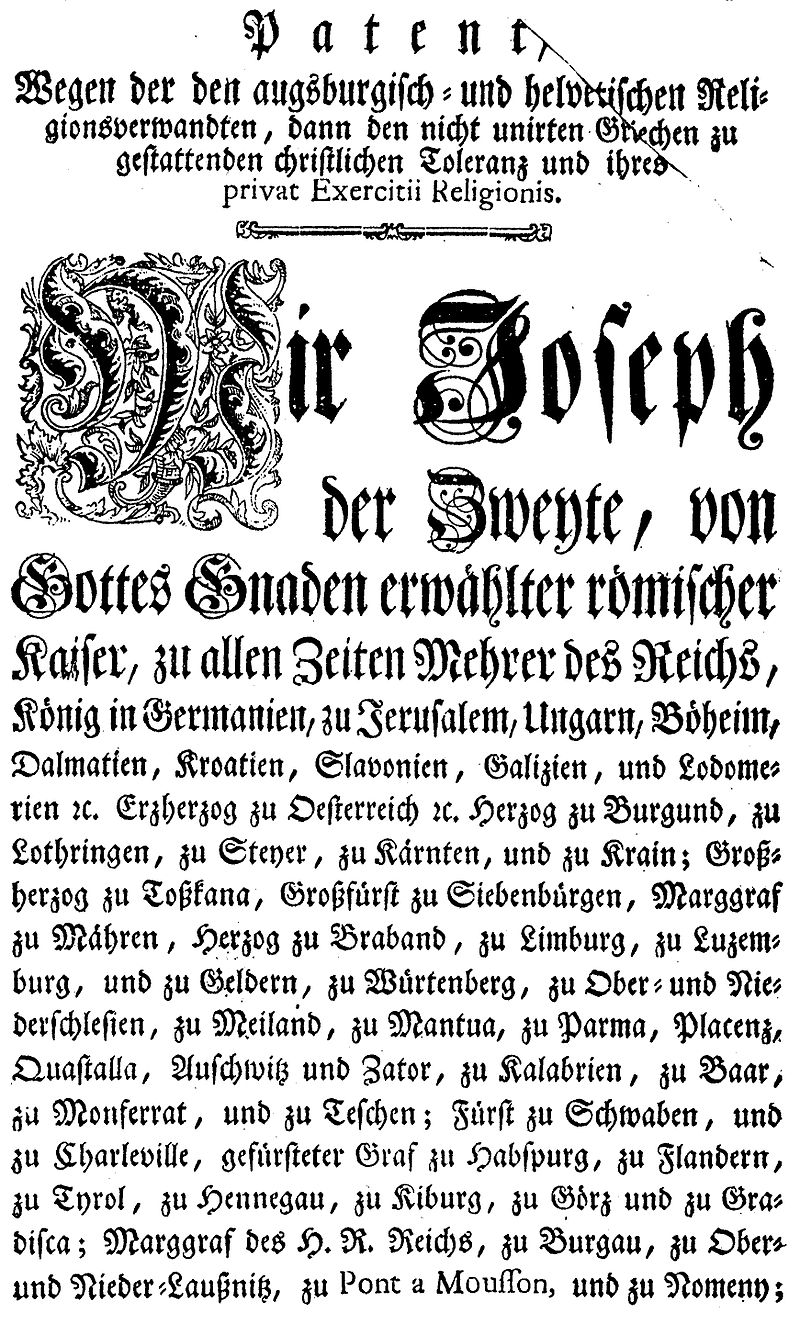

Patent of Toleration – 1781 – Wien

Fact of the Hungarian figure „Edict of Torda – 1568”

Part of the „Religious tolerance and intolerance” topic

The Patent of Toleration, issued by Emperor Joseph II on October 13, 1781, was a significant step towards religious reform in the Habsburg Monarchy. Part of the broader Josephinist reforms, the Patent extended limited religious freedom to non-Catholic Christians, including Lutherans, Calvinists, and the Eastern Orthodox, in a monarchy that had long been dominated by Catholicism. While it did not offer full religious equality, the decree was a notable shift, marking the first time since the Counter-Reformation that the practice of non-Catholic religions was legally recognized.

Under the Patent, members of minority faiths were permitted to hold private religious exercises, although these had to take place in non-public spaces, often referred to as clandestine churches. The decree allowed for the construction of so-called „houses of prayer” (Bethäuser), which could not resemble traditional church buildings. Worship was still tightly regulated, and key sacraments like marriage were reserved for the Catholic Church. Nevertheless, Protestant communities, particularly in regions like Upper Austria, Styria, and Carinthia, began to rebuild their religious institutions, relying heavily on their crypto-Protestant traditions, which had survived underground for over a century.

The Patent of Toleration also addressed the issue of mixed-faith marriages, a matter that had been contentious in the Habsburg Empire. The decree introduced regulations stipulating that if the father in a mixed-faith marriage was Catholic, all children had to be raised in the Catholic faith. If the mother was Catholic, only the daughters were required to be raised as Catholics. These regulations foreshadowed Joseph II’s Marriage Patent of 1783, which sought to bring marriages under civil law rather than canon law.

The Patent of Toleration is often seen as a precursor to broader reforms, including the Edict of Tolerance for Jews in 1782, which extended certain freedoms to Jewish communities. However, the edict imposed restrictions as well, such as requiring Jews to establish German-language schools and sending their children to Christian schools if no Jewish schools were available. It also abolished the autonomy of Jewish communities, introduced military conscription for Jewish men, and required Jews to adopt family names.

Although the Patent was a groundbreaking move towards religious tolerance, it maintained significant limitations. Non-Catholic Christians still faced restrictions, especially in the public expression of their faith, and the Unity of the Brethren was still suppressed. Full religious equality would not come until much later. For example, it wasn’t until the Protestantenpatent of 1861 under Emperor Franz Joseph I that Protestants were granted a legal status equal to that of the Catholic Church.

In the broader context of Central Europe, the Patent of Toleration reflects the complex history of religious reform and the slow but significant progress toward pluralism. Much like the earlier Edict of Torda (1568), the Patent was an important milestone in the gradual acceptance of religious diversity. Both decrees, although separated by centuries, played critical roles in shaping the religious landscape of Central Europe, laying the groundwork for more inclusive societies. However, true freedom of religion, as we understand it today, remained an aspiration, with various communities continuing to face limitations and inequalities well into the 19th century.