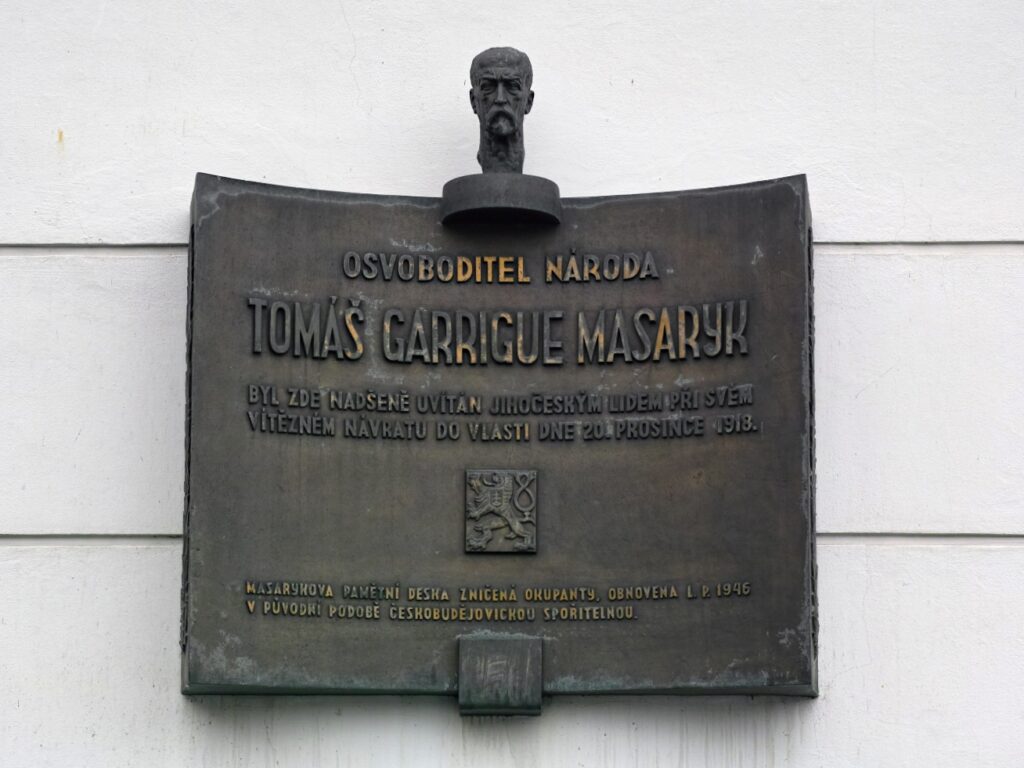

“The arrival of Masaryk from war exile to independent Czechoslovakia – České Budějovice

Czech figure of the „Creation of the modern states (1918-1920)” topic

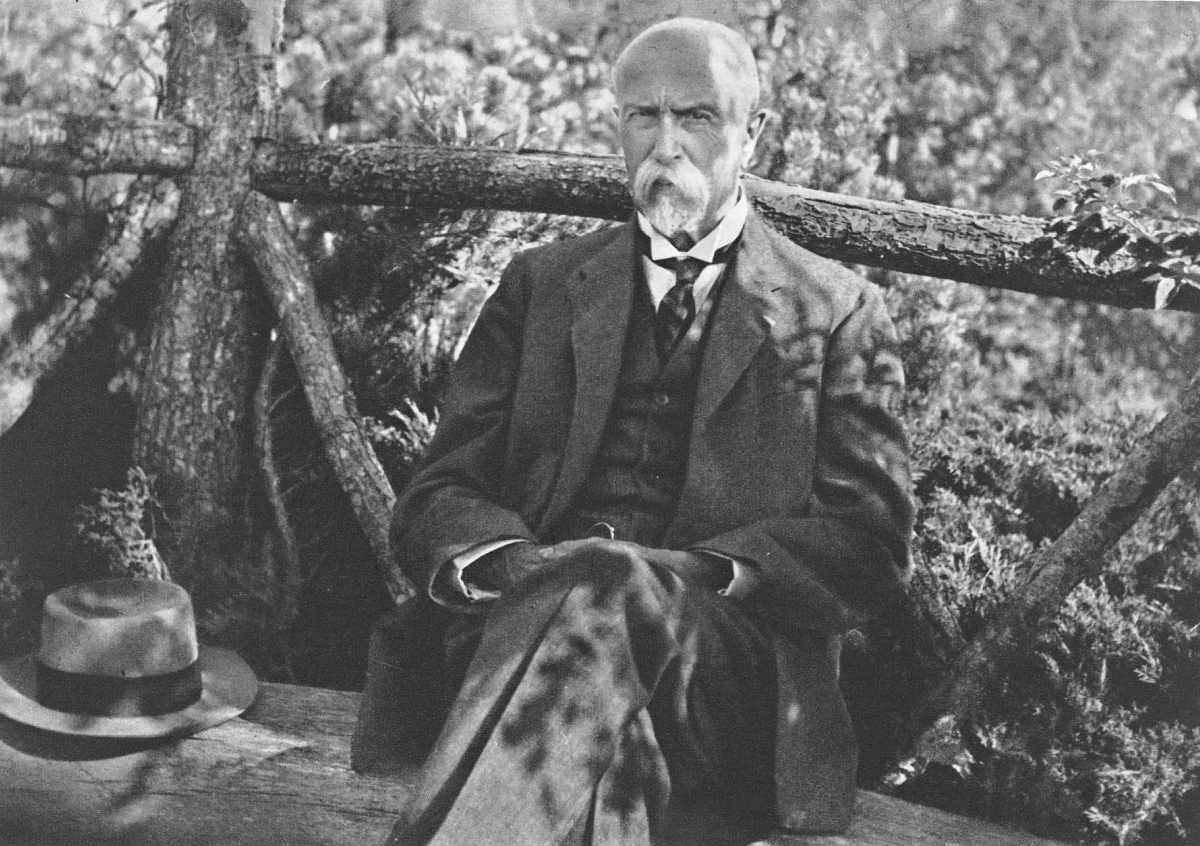

At the beginning of the First World War, the parliament in Austria-Hungary was closed and democratic rights were restricted. As a result of state repression, most Czech politicians were pushed into passivity. Tomáš G. Masaryk went into exile at the end of 1914 and attempted something radically new – he declared a fight for an independent Czech state. The largely hopeless position was reinforced by Czech propaganda in the French and British media. Masaryk was in France joined by the Czech Edvard Beneš and the Slovak Milan Rastislav Štefánik, where they formed an anti-Austrian resistance organisation – the Czechoslovak National Council. Upon his return home four years later in December 1918, Masaryk returned to an independent new state, having already been elected as the first Czechoslovak president.

Efforts for an independent state of Czechs and Slovaks (‘Czechoslovaks’ in Masaryk’s concept) would have been futile without foreign troops – the legions – which were formed in the states of the Triple Entente from Czech and Slovak emigrants, captives and defectors. Thanks to the legions, the Triple Entente recognised the nascent Czechoslovakia as an allied state at war with the Central Powers in 1918. The writer Jaroslav Hašek was also a legionnaire, and he translated his wartime experience into his world-famous book The Good Soldier Švejk.

After four years of war, Austria-Hungary collapsed, and Czechoslovakia was proclaimed on 28 October 1918. The enthusiasm was complemented by a general conviction to do away forever with everything that resembled Austria and the Habsburgs. Imperial symbols were removed as well as statues of the recently deceased Franz Joseph I and the Enlightenment monarch Joseph II, considered a Germanizer, were torn down. In Old Town Square, the baroque Marian Column, allegedly a symbol of the „oppression of the Habsburgs” after the Battle of White Mountain, was demolished. One of the first democratic laws of the new republic concerned the stripping the old elites of privileges – in December 1918, noble titles and orders were abolished. But the land reform, which redistributed large land properties in favour of small farmers and landless people, affected the lives of the old elites much more.

The organization of Europe after the First World War was supposed to be guided by the principle of national self-determination, but given the national diversity of Central Europe, its application was hardly possible. The new Czechoslovakia had to cope with the fact that alongside the Czechoslovaks (Czechs and Slovaks), large ethnic groups of Germans and Hungarians and smaller groups of Rusyns, Poles and Jews lived within its borders. Attempts of the areas inhabited by Germans to secede from Czechoslovakia and ethnic divisions burdened not only the first years of the republic. The failure to resolve them amicably was one of the causes of its demise after twenty years.

Facts