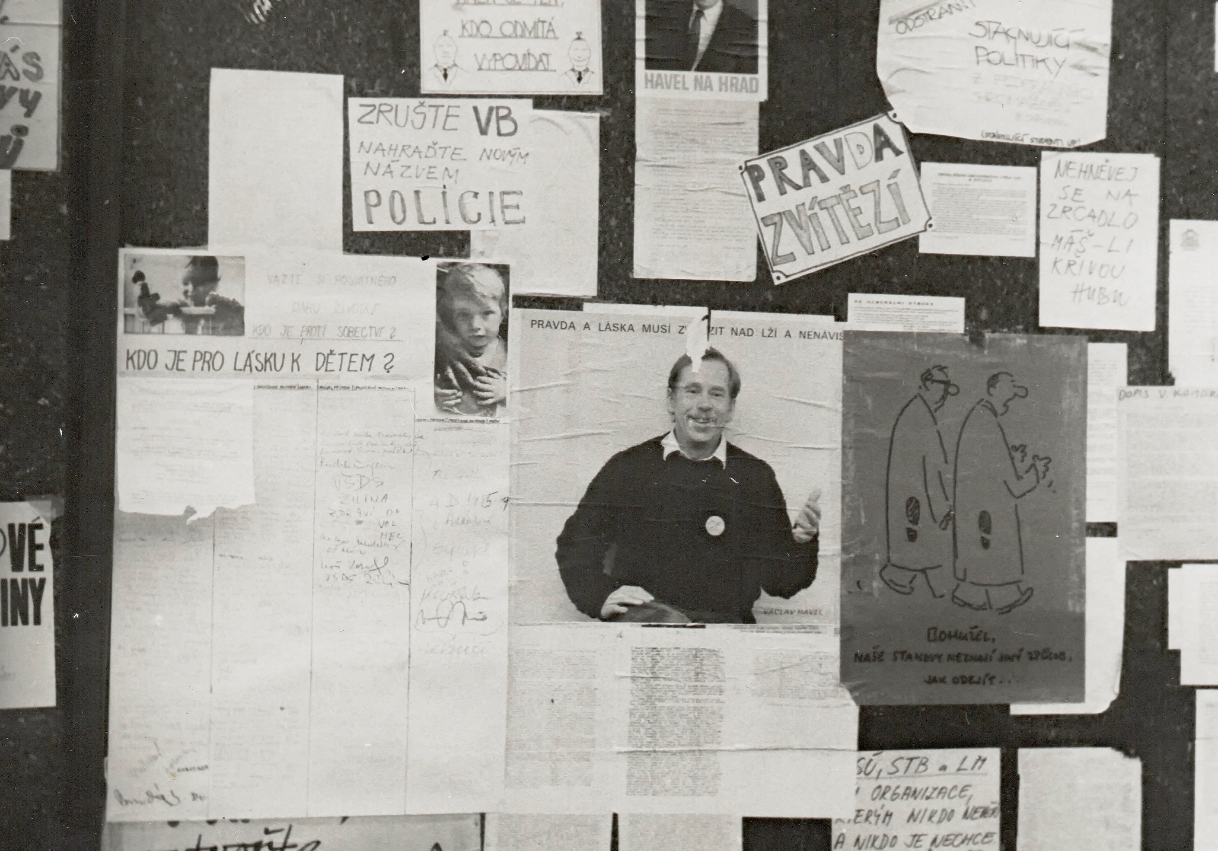

Velvet revolution – 1989 – Prague, Wenceslas Square

Czech figure of the „Dreaming about the democracy” topic

The year 1989 is considered the year of miracles in Central Europe – annus mirabillis. Like a house of cards, the communist dictatorships collapsed. Since November 1989, the rule of law, respect for civil liberties and human rights, political pluralism and free elections have also begun to return to Czechoslovakia. The 1990’s then saw economic reforms that rehabilitated the principles of free enterprise and introduced market capitalism with all its benefits and drawbacks.

No one in the West anticipated the Soviet system in Central Europe to collapse in 1989. The question of why this happened is not easy to answer, but we know that the economic crisis related to the political crisis of state socialism in Czechoslovakia in the second half of the 1980’s had been deepening for a long time. Mikhail Gorbachev’s attempt to reform the communist system in the USSR, which was intended to open up a lagging Soviet society to freer thinking and inspiration from around the world, was very reminiscent of the Prague Spring. However, the aging communist establishment in Prague, which had been in power as a result of the Soviet occupation, was unable and unwilling to respond positively to Gorbachev’s suggestions. Unlike Poland, Hungary, and even East Germany, in Czechoslovakia it seemed as if time had stopped in 1970.

Compared to 1970, something has yet changed. For more than a decade, groups of dissent and resistance had been informally organized, bringing together those who had been outclassed by the normalization regime because they refused to participate in the dictatorship by repudiating the ideals of 1968 for career reasons. Among the leading representatives of „dissent”, being a space of independent thought, was the world-famous playwright Václav Havel, one of the initiators and early spokesmen of Charter 77. Havel gradually became a living symbol of resistance to “normalisation”. State security authorities tried to imprison, intimidate or at least isolate dissidents from domestic society. Nevertheless, they did not keep to themselves but made contacts with like-minded people in neighbouring countries. They met with the Poles during coordinated ascents of Sněžka in Krkonoše mountains and camouflaged their meetings as tourism in the face of the authorities’ scrutiny.

However, the Velvet Revolution of 1989 was not initiated by dissent. Anti-regime demonstrations in Prague and various non-communist demonstrations had been going on for at least a year before. The impulse for nationwide demonstrations against the Communist Party’s rule came from university students. The brutal police suppression of a non-violent student march on Národní třída in Prague on 17 November, the day of the commemoration of the Nazi terror against Czech university students, shocked Czech-Slovak society and aroused it to mass expressions of dissent. Around dissidents, students and actors, the Civic Forum was formed in Prague and the Public Against Violence in Bratislava to push for democratic changes and organise a general strike. In December 1989, Václav Havel became President of Czechoslovakia and after more than forty years the communist regime was on its knees.

Further reading:

Pánek, Jaroslav – Tůma, Oldřich (eds.), History of the Czech Lands, Prague 2018, p. 593-624.

Williams, Kieran, The Prague Spring and its Aftermath: Czechoslovak Politics, 1968-1970, Cambridge 1997.

Koudelka, Josef. Invasion 68, Paris 2008.

Blažek, Petr – Eichler, Patrik – Jareš, Jakub, Jan Palach ’69, Praha 2009.

Facts