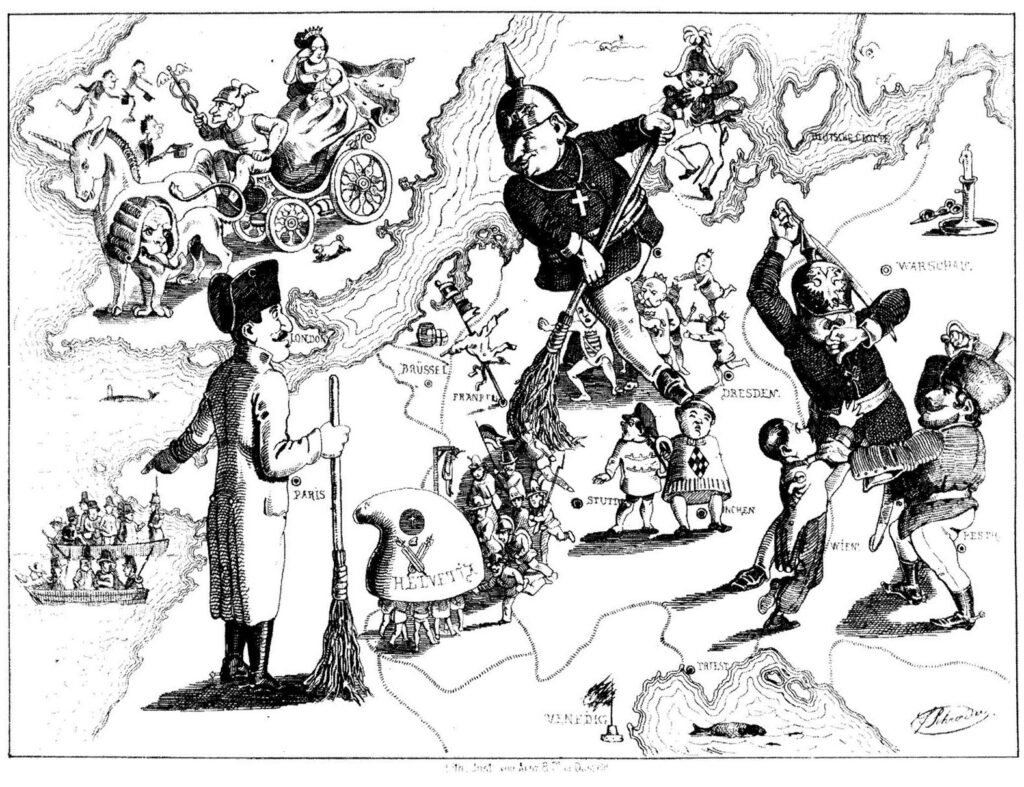

The Revolutions of 1848, often referred to as the „Springtime of Nations,” were the most widespread revolutionary wave in European history, spanning 1848 to 1849. These uprisings were triggered by a complex web of liberal and nationalist aspirations, socioeconomic pressures, and a widespread yearning for constitutional reform. Sparked by the February Revolution in France, the revolutionary fervor quickly engulfed over fifty state entities across Europe, including the Habsburg Empire, the German Confederation, and the Italian states.

The Hungarian Revolution of 1848 began in Pest, where the iconic National Museum became a rallying point for reformists. The bloodless events of March 15th, 1848, symbolized the peaceful aspirations of a modern political nation. Key figures like Lajos Kossuth and Sándor Petőfi emerged as revolutionary icons, pushing for constitutional governance and independence from the Habsburg Empire. Kossuth’s fiery speeches in the Diet of Pozsony (now Bratislava) culminated in the April Laws, which granted Hungary significant autonomy under the Crown.

In Bohemia, the revolution also signaled the emergence of a modern political nation. The St. Wenceslas Committee, convened in Prague, demanded civil liberties and national rights, presenting these demands directly to Emperor Ferdinand. The Slavic Congress held in Prague further highlighted the diversity of aspirations within the Habsburg lands, as Slavic leaders debated visions of federalism and Slavic unity amidst revolutionary upheaval.

Sándor Petőfi, born in Kiskőrös, epitomized the romantic ideals of the revolution. As a poet and revolutionary, his works, including the stirring „National Song,” became anthems of the Hungarian struggle. Petőfi’s life and legacy underscored the cultural dimension of 1848, emphasizing the role of literature and art in shaping national consciousness.

The revolution’s early successes, such as the Battle of Pákozd on September 29, 1848, bolstered Hungarian morale. This military victory demonstrated Hungary’s resolve to defend its newly won autonomy. However, setbacks like the Battle of Schwechat in October 1848 marked the shift from political reform to full-scale war for independence.

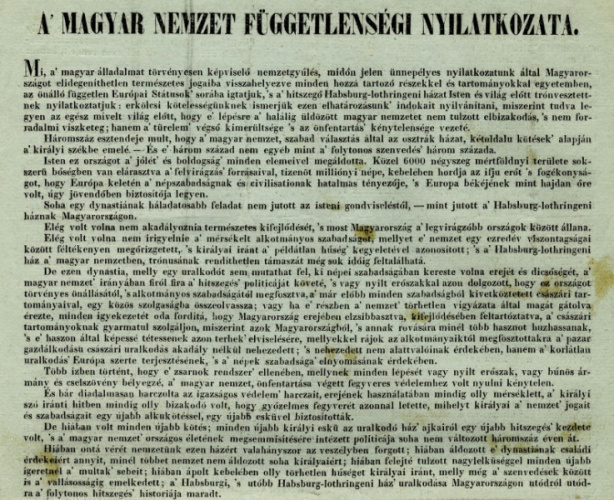

As the revolution evolved into a war of independence, Debrecen became a symbolic and strategic center. Declared the temporary capital, Debrecen hosted the historic Declaration of Independence on April 14, 1849. This bold proclamation severed ties with the Habsburg monarchy, cementing Hungary’s determination to stand as a sovereign nation.

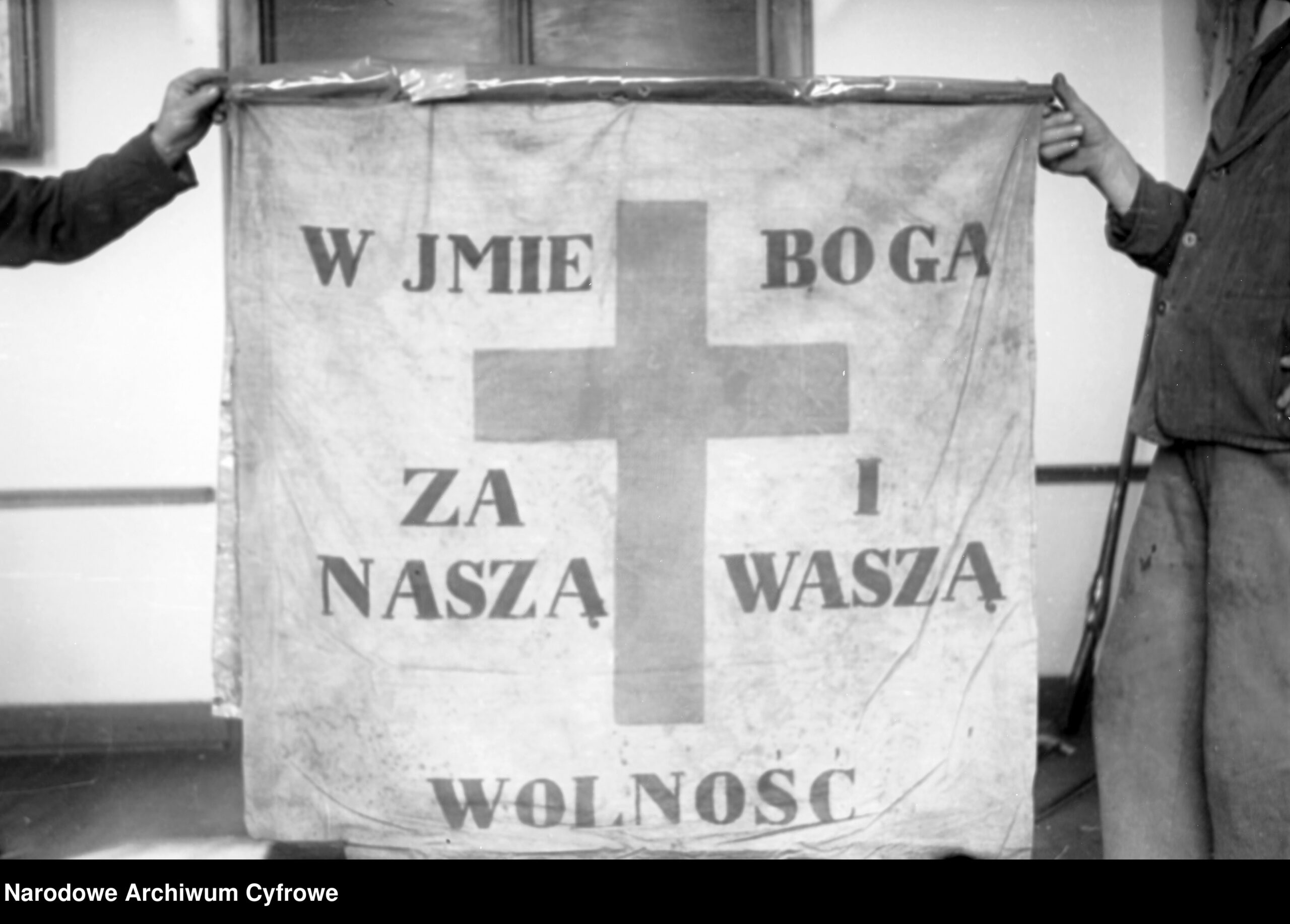

The Declaration of Independence reflected broader European aspirations for self-determination. Similar sentiments were evident in Polish territories, where uprisings in Tarnów and Lvov mirrored Hungarian struggles. General Józef Bem, a Polish national hero, played a significant role in the Hungarian war effort, exemplifying the transnational solidarity that characterized 1848.

Despite its early promise, the Hungarian Revolution faced insurmountable challenges. The intervention of Tsar Nicholas I and the Russian army decisively tipped the scales. The capitulation at Világos on August 13, 1849, marked the revolution’s tragic end, with Hungarian forces overwhelmed by combined Austrian and Russian might.

The aftermath was brutal. The execution of the 13 Martyrs of Arad on October 6, 1849, became a symbol of national sacrifice. These generals, hailing from diverse ethnic backgrounds—including Germans, Hungarians, Serbs, and Croats—underscored the revolution’s inclusive nature. Their martyrdom is commemorated annually, reflecting their enduring place in Hungarian memory.

The impact of the 1848 revolutions extended beyond Hungary. In Prague, figures like František Palacký articulated visions of federalism and national self-determination, laying the groundwork for modern Czech identity. Similarly, the Kroměříž Parliament sought to reshape the Habsburg monarchy, though its efforts were ultimately stymied by imperial repression.

In Polish territories, revolutionary fervor bridged earlier and later uprisings. The events in Poznań and Lvov highlighted the persistent struggle for Polish independence, while the abolition of serfdom in Galicia reflected broader social transformations spurred by 1848.

The Revolutions of 1848 remain a defining moment in Central European history, uniting diverse nations in a shared struggle for liberty and self-determination. From the Hungarian Declaration of Independence in Debrecen to the Slavic Congress in Prague, these events underscored the universal aspirations for freedom that transcended borders. The legacy of 1848 continues to inspire, reminding us of the enduring power of collective action and the quest for justice.

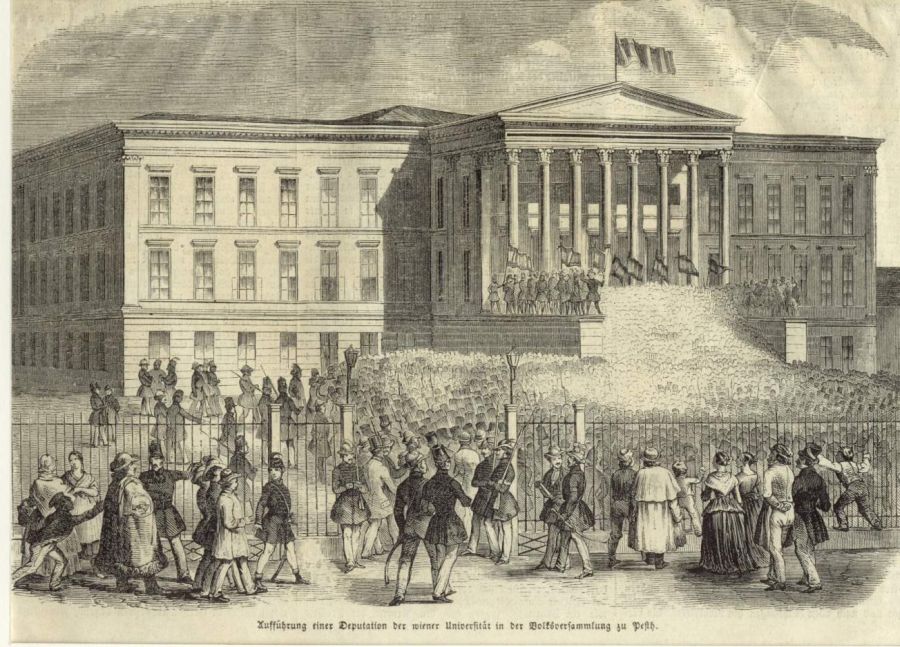

Bloodless Revolution in Pest – The birth of the political nation – National Museum, Budapest

The National Museum in Budapest holds a pivotal place in Hungarian history as the symbolic epicenter of the Bloodless Revolution of 1848, which marked the birth of the modern Hungarian political nation. On March 15, 1848, in the shadow of this neoclassical landmark, the people of Pest rallied to demand civil liberties, national sovereignty, and the end of feudal privileges—a movement that echoed across Central Europe in solidarity with the broader revolutions of 1848.

Hungarian independence from the Habsburg dynasty – Debrecen

The second phase of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 witnessed the escalation of the struggle into an all-out War of Independence. This period, defined by intense military campaigns and radical political decisions, reached a symbolic zenith in Debrecen, the temporary seat of the Hungarian government, where the Declaration of Independence was issued on April 14, 1849.

Lvov-Tarnów-Poznan – Monument of Sándor Petőfi, Tarnów

The Springtime of Nations, a series of national revolutions in 1848-1849, covered almost all of the Europe. In Polish history, this particular time fell between the November (1830-1831) and the January (1863-1864) Uprisings. Repressions which the population suffered after the previous rebellions were still fresh in its memory, and the generation that was supposed to begin the next revolt was only just coming of age. Nevertheless, certain actions – although uncoordinated with each other – inspired by foreign political upheavals were also taken in the Prussian and Austrian partitions, especially in the cities of Lviv and Poznań.

The Birth of a Political Nation – Prague

The Revolution of 1848 hit almost all of Europe and the Habsburg monarchy along with the Czech lands were no exception to this. The demands of Czech revolutionaries revolved around calls for civil liberties and national rights and through their activities, the modern political nation began constituting during the revolutionary years. Influences from the revolutionary movements in France, Italy and Germany prompted liberal and democratically minded political and cultural representatives from Bohemia to convene at the St. Wenceslas Spa in Prague on 11 March 1848 . The St. Wenceslas Committee, a delegation of liberal and democratically minded political and cultural representatives from Bohemia, signed a petition that called for the liberalisation of the political system. The petition was presented to the Austrian Emperor in Vienna. While both Czech and German representatives were present at the St. Wenceslas Spa, their subsequent actions diverged during the events of 1848. This event marked the beginning of the revolution in Bohemia and can be seen as the symbolic birth of a modern Czech political nation.