Stephen, the King rock opera – National emotions in communism – Budapest, City Park

Hungarian figure of the „Culture against communism” topic

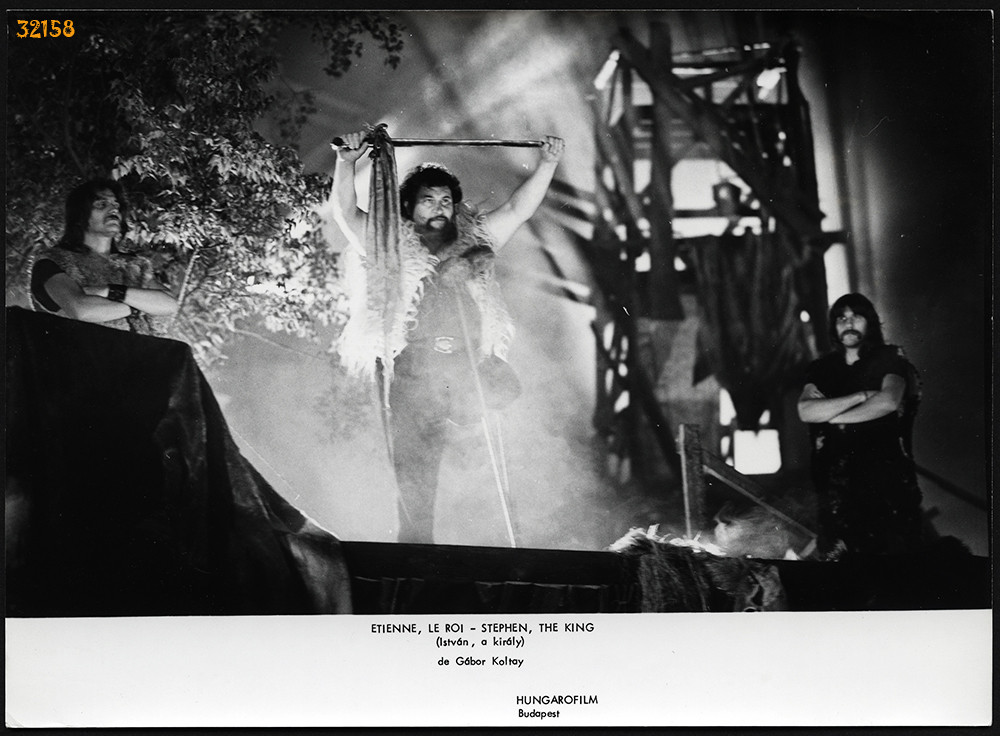

The rock opera Stephen, the King (István, a király) stands as a cornerstone of Hungarian cultural heritage, blending history, music, and national sentiment. Composed by Levente Szörényi with lyrics by János Bródy, the opera was based on Miklós Boldizsár’s drama Ezredforduló (Turn of the Millennium). Premiering on August 18, 1983, on the newly named Királydomb (King’s Hill) in Budapest’s City Park, this outdoor performance became an immediate sensation, combining profound storytelling with vibrant musical compositions. Lorenz Klotz’s evocative set design and the cinematic adaptation further elevated the production to legendary status.

The narrative centers on the posthumous power struggle following the death of Géza, Grand Prince of Hungary, between his Christian successor István (Stephen) and the pagan chieftain Koppány. Structured into four acts—The Heritage, Esztergom, Koppány, and Stephen the King—the opera explores themes of faith, loyalty, and the difficult path toward unification. The music, including iconic pieces like “Te kit választanál?” (Who Would You Choose?), “Oly távol vagy tőlem” (You Are So Far Away Yet So Close), and “Felkelt a napunk” (Our Sun Has Risen), continues to resonate with audiences for its emotional depth and timeless relevance.

The characters embody opposing visions for Hungary’s future. István represents the adoption of Christianity and alignment with Western Europe, while Koppány champions the preservation of pagan traditions and independence. Through dynamic interactions, the story reflects Hungary’s historical struggles between maintaining tradition and embracing progress—a theme that resonates beyond its medieval setting. The performance’s timing during the Communist regime amplified its impact. Ostensibly about medieval history, Stephen, the King carried undertones of national pride and defiance against external dominance, subtly challenging the ideological conformity of the era. The opera’s ability to invoke Hungarian identity and cultural autonomy became a source of empowerment for audiences, positioning it as a cultural milestone.

The choice of Stephen I, canonized as a saint and viewed as the founder of the Hungarian state, as the opera’s protagonist was no coincidence. His legacy as a unifier and a protector of Hungary’s independence contrasted starkly with the reality of Soviet-imposed rule. While the storyline focused on events from medieval Hungary, its themes of resistance, national identity, and the tension between tradition and change struck a chord with contemporary audiences. The performance of Stephen, the King was not overtly political, but its underlying message of cultural pride and independence was unmistakable.

The phenomenon of using culture as a medium for resistance was not unique to Hungary. Across Central Europe, artists, musicians, and filmmakers found ways to critique or undermine Communist ideology while evading censorship. In Poland, for example, the plays of Jerzy Grotowski and the music of Czesław Niemen echoed themes of spiritual and national defiance. In Czechoslovakia, the films of the Czech New Wave, including Milos Forman’s The Firemen’s Ball, highlighted the absurdities of bureaucratic socialism. These creative efforts fostered a shared sense of identity among Central European nations, uniting them in their struggle against cultural oppression.

Hungary’s rock opera movement was particularly innovative. In the same era as Stephen, the King, other musical productions addressed themes of freedom and social justice, often drawing on historical narratives. These performances became cultural landmarks, offering a form of escape and solidarity for audiences yearning for greater autonomy. The enduring popularity of Stephen, the King highlights its role as more than just entertainment; it was a unifying cultural event that helped sustain national pride during a difficult period.

Facts