Bloodless Revolution in Pest – The birth of the political nation – National Museum, Budapest

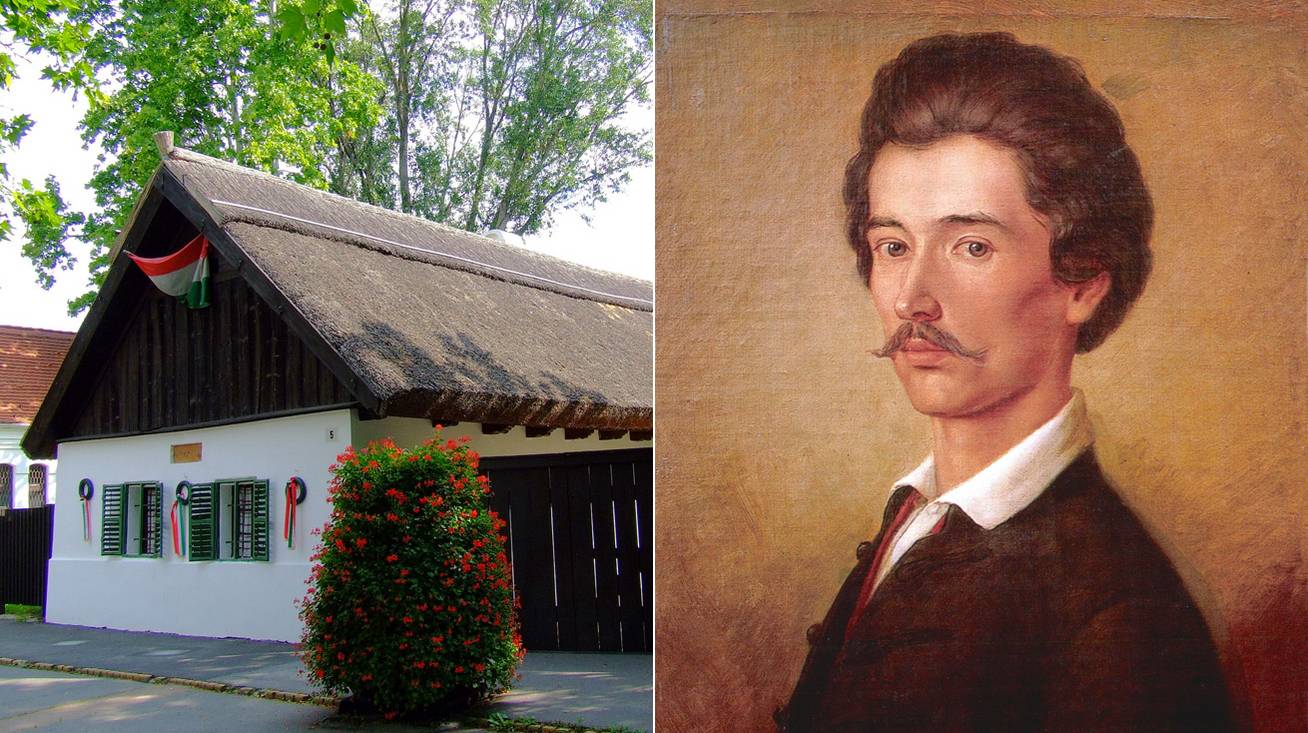

Hungarian figure of the „Revolutions of 1848„ topic

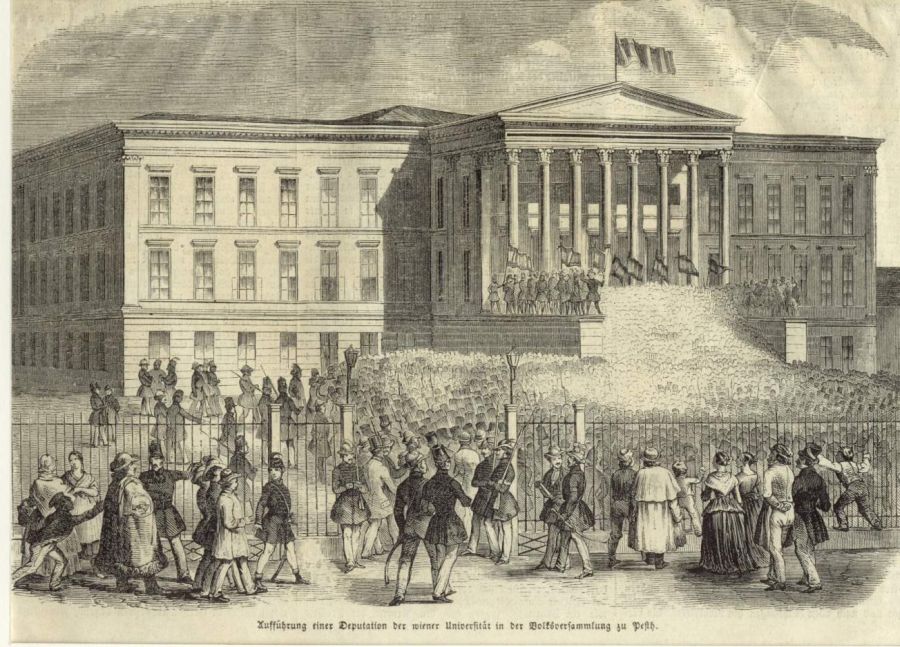

The National Museum in Budapest holds a pivotal place in Hungarian history as the symbolic epicenter of the Bloodless Revolution of 1848, which marked the birth of the modern Hungarian political nation. On March 15, 1848, in the shadow of this neoclassical landmark, the people of Pest rallied to demand civil liberties, national sovereignty, and the end of feudal privileges—a movement that echoed across Central Europe in solidarity with the broader revolutions of 1848.

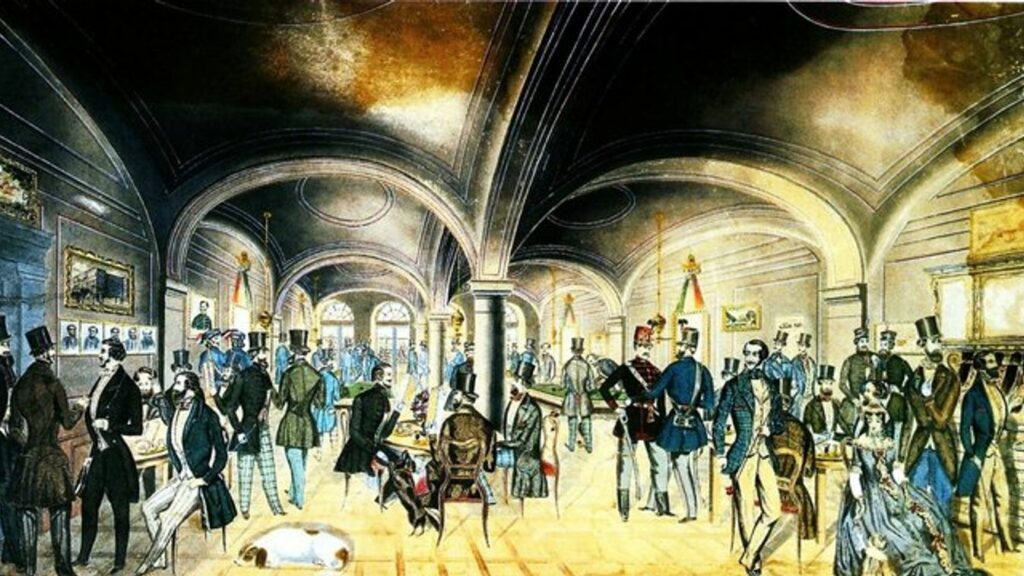

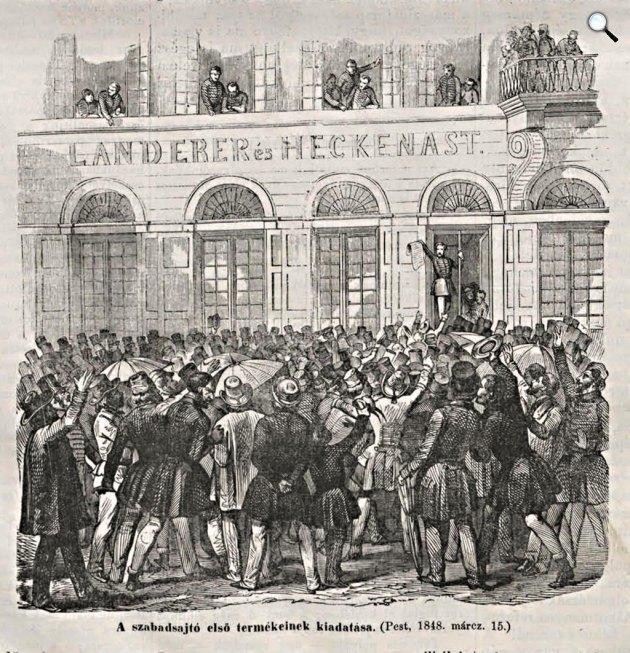

The revolution began with the recitation of Sándor Petőfi’s stirring National Song („Talpra Magyar!”) on the museum steps, a powerful call to action that became the anthem of the uprising. This act, along with the reading of the Twelve Points, a manifesto demanding constitutional reform and press freedom, galvanized support across social classes. The events in Pest remained largely peaceful, earning it the moniker „Bloodless Revolution.” The revolutionaries, gathering at the Pilvax Coffee House, seized control of the Landerer Printing Press to distribute their demands, and later freed Mihály Táncsics, a political prisoner, in a series of symbolic acts that embodied the revolutionary spirit of March 15, 1848. The lack of violence distinguished Hungary’s early efforts for change from the often-violent upheavals elsewhere in Europe, particularly in Vienna, Berlin, and Prague.

The revolution’s broader significance lay in its assertion of Hungary’s political and cultural distinctiveness within the Habsburg Monarchy. While Budapest served as the movement’s nerve center, Pozsony (Bratislava) hosted the last Hungarian Diet, which played a crucial role in passing progressive legislation, including the abolition of serfdom. These reforms resonated with similar efforts in Bohemia and Poland, where national identity and self-determination became rallying cries.

Central to the revolution was its connection to Central European unity and discord. Leaders like Lajos Kossuth maintained close ties with reformers in Vienna and Prague, advocating for constitutionalism across the empire. Yet, this period also exposed fractures within the multinational Habsburg lands, as ethnic tensions among Hungarians, Slovaks, Croats, and Romanians sometimes undermined shared aspirations for freedom. The revolution’s suppression, culminating in the defeat at Schwechat in October 1848, reflected the complexity of these dynamics.

The National Museum remains a symbol of Hungary’s enduring quest for liberty. Its role in the 1848 Revolution highlights the intersection of national identity and collective Central European struggles for self-determination, making it a site of remembrance not only for Hungary but for the shared history of a region striving to define its place in modern Europe.

Facts