The Birth of a Political Nation – Prague

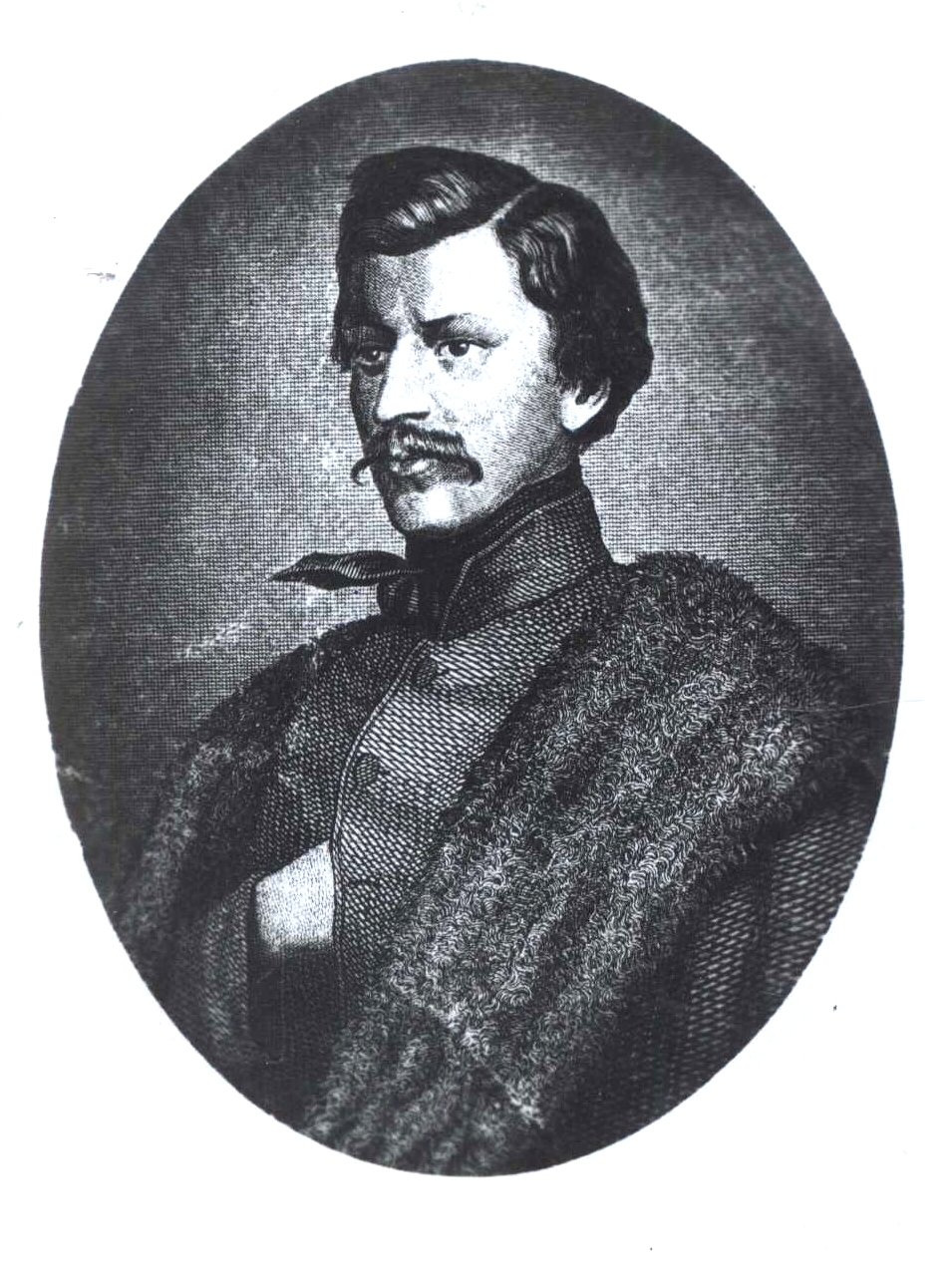

Czech figure of the „Revolutions of 1848„ topic

The Revolution of 1848 hit almost all of Europe and the Habsburg monarchy along with the Czech lands were no exception to this. The demands of Czech revolutionaries revolved around calls for civil liberties and national rights and through their activities, the modern political nation began constituting during the revolutionary years. Influences from the revolutionary movements in France, Italy and Germany prompted liberal and democratically minded political and cultural representatives from Bohemia to convene at the St. Wenceslas Spa in Prague on 11 March 1848 . The St. Wenceslas Committee, a delegation of liberal and democratically minded political and cultural representatives from Bohemia, signed a petition that called for the liberalisation of the political system. The petition was presented to the Austrian Emperor in Vienna. While both Czech and German representatives were present at the St. Wenceslas Spa, their subsequent actions diverged during the events of 1848. This event marked the beginning of the revolution in Bohemia and can be seen as the symbolic birth of a modern Czech political nation.

One of the demands of numerous revolutionary movements was the opposition to the absolutist regime and the call for a constitution. Just shortly after the revolution broke out in the Habsburg monarchy, Emperor Ferdinand was forced to promise a constitution. To draft one, the Constituent Assembly was convened, originally in session in Vienna but later relocated to the Archbishop’s Palace in Kroměříž, where a memorial plaque marks its importance till nowadays.

While the fight against absolutism united many national revolutionary movements, nationalism and the overlapping demands stemming from it placed these movements in opposition to one another. For instance, efforts to unite Germans into a single state faced resistance from leaders of the Czech revolutionary movement. This opposition is perhaps best exemplified by the famous letter from František Palacký, known as the „Letter to Frankfurt,” in which he rejects the inclusion of the Czech lands in a united Germany.

Nationalist emotions were also aroused by the Slavic Congress, which convened in Prague on June 2nd to address not only the relations between the Slavic nations within the Habsburg Monarchy but also the efforts to unite Germany and the Hungarian effort in establishing an independent Hungarian Kingdom.

The revolution even affected rural society, which focused mainly on the issues of their daily life related to servitude and labour obligations. The proposal to abolish the estate-based division of society was presented on July 24, 1848 by the youngest member of the Reichstag, Hans Kudlich, and a few months later, servitude and the patrimonial administrative system were abolished.

The press played a pivotal role during the revolution as it served as the chief promulgator of ideas and as the organiser of public life, which allowed it to influence political events. Its hitherto unprecedented development during the revolutionary era laid the foundations for modern Czech journalism, with which the journalist and writer Karel Havlíček Borovský is inherently linked.

Nonetheless, while the legacy of the revolution shaped the following decades of development within the Habsburg Monarchy, the revolutionary events of years 1848/49 do not resonate as vigorously in contemporary Czech collective memory as they would in other Central European countries. The buildings of the St. Wenceslas Spa were demolished in the last quarter of the 19th century and a completely new street was constructed in their place. As a result, the plaque commemorating the beginning of the 1848 revolution, erected in 1928, is now situated inside a building (now a primary school) that has only a distant connection to the events and is hardly accessible to the general public.

Facts