The First Christian Saints and the Formation of National Identity in Central Europe: Hungary, Poland, and Czechia

The early medieval period in Central Europe was marked by the spread of Christianity, a transformative force that shaped the cultural, political, and religious landscapes of the region. In Hungary, Poland, and Czechia, the veneration of Christian saints played a central role in the consolidation of new kingdoms and the formation of national identities. These saints, many of whom were rulers or prominent figures of their time, became symbols of unity, faith, and resistance, leaving a lasting legacy that continues to resonate in these nations today.

In Hungary, the Christianization process was closely linked to the figure of St. Stephen (Szent István), the first king of Hungary. Crowned in Esztergom in 1000 AD, St. Stephen is revered as the founder of the Hungarian state and the one who established Christianity as the kingdom’s official religion. His efforts to convert the Hungarian tribes to Christianity were supported by the establishment of numerous bishoprics, including the first bishopric in Veszprém, which became the center of the Queens of Hungary, underscoring the integration of religious and royal authority. The royal crypt in Székesfehérvár, where many Árpád kings were buried, further symbolizes the connection between the monarchy and the church.

One of the most cherished relics associated with St. Stephen is the Holy Right Hand (Szentjobb), a symbol of divine favor and a national treasure. The Holy Right Hand, believed to be the mummified right hand of the king, is preserved in Szentjobb (Sâniob) and is the focal point of national veneration, especially during the annual St. Stephen’s Day celebrations. The Legend of the Holy Crown, housed in the Parliament building in Budapest, further reinforces the divine legitimacy of the Hungarian monarchy, symbolizing the unity and continuity of the Hungarian state.

Hungary’s Christian heritage also includes St. Emeric, the pious son of St. Stephen, who is venerated at Pannonhalma, one of the oldest monastic communities in the country. Saints Andrew-Zorard and Benedict, hermits who lived on Zobor Hill, and Saint Maurus, the author of their legends, are other key figures in Hungary’s early Christian history. St. Gerard (Gellért), a martyr who played a crucial role in the Christianization of Hungary, is commemorated on Gellért Hill in Budapest, where he was killed during a pagan uprising in 1046. St. Ladislaus, another important Hungarian saint, is venerated in Nagyvárad (Oradea) and Győr, where his relic, the Herma of Saint Ladislaus, is preserved, reflecting his status as a warrior king and patron saint.

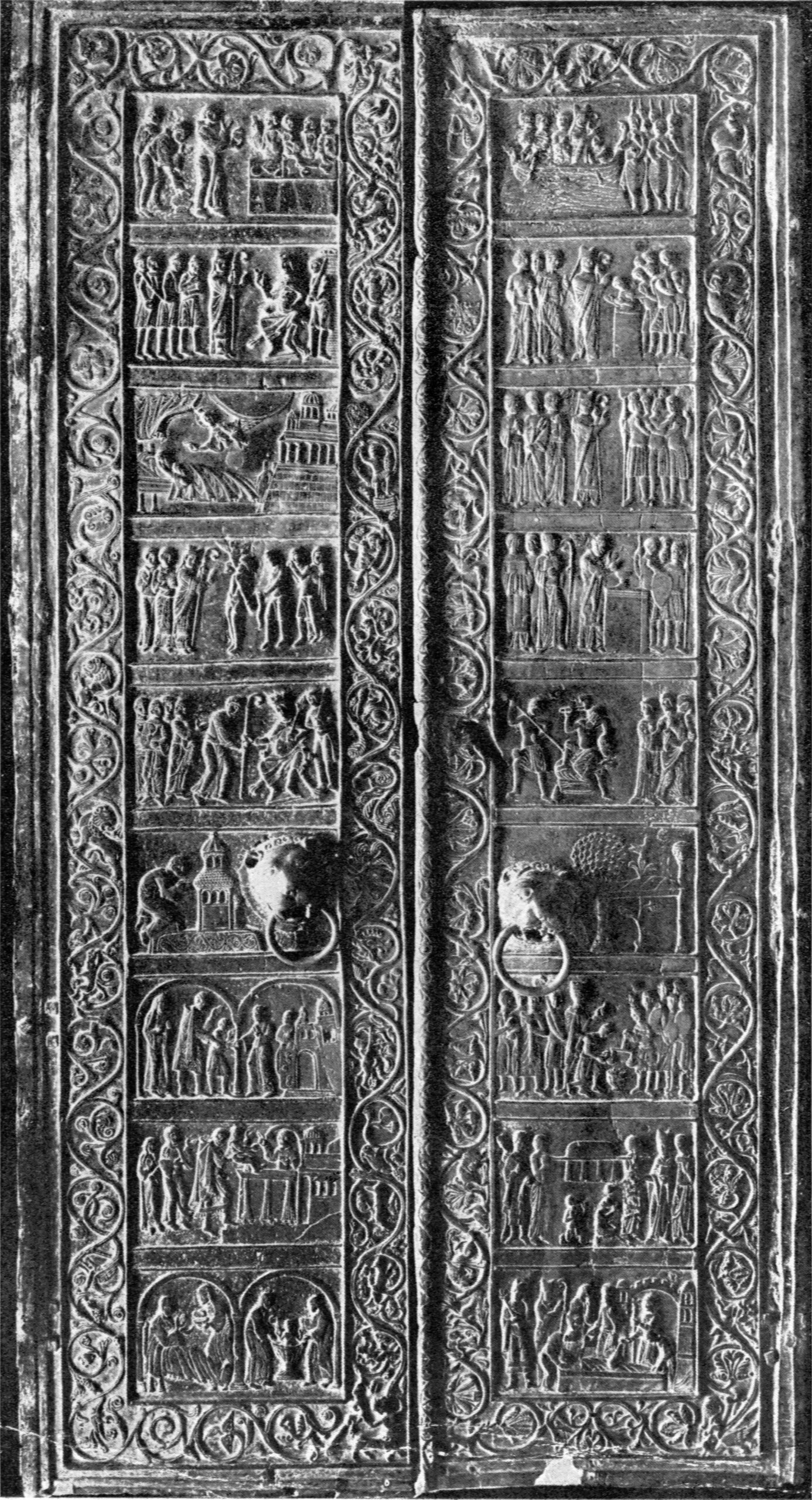

In Poland, St. Adalbert (Święty Wojciech) is a central figure in the nation’s Christian history. After serving as the Bishop of Prague, Adalbert undertook missionary work in pagan Prussia, where he was martyred in 997 AD. His body was ransomed by the Polish Duke Bolesław I the Brave and buried in Gniezno, which became a significant religious center. The Gniezno Doors, which depict scenes from Adalbert’s life, are a masterpiece of Romanesque art and symbolize Poland’s Christian heritage. St. Adalbert’s influence extends to Częstochowa, home to the Black Madonna, one of Poland’s most important religious icons, and Kraków’s Wawel Cathedral, where he is honored alongside St. Stanislaus, another key Polish saint.

In Czechia, St. Wenceslas (Svatý Václav) is revered as the patron saint of Bohemia and a symbol of Czech statehood. Born into the Přemyslid dynasty, Wenceslas was known for his piety and efforts to spread Christianity. His martyrdom in 935 AD, at the hands of his brother Boleslaus, elevated him to the status of a martyr, and he became a symbol of Christian virtue and Czech identity. Prague, the capital of Czechia, is deeply connected to the veneration of St. Wenceslas, with his statue in Wenceslas Square serving as a national symbol. His relics are housed in St. Vitus Cathedral, further underscoring his enduring influence on Czech culture and history. St. Adalbert, who also served as the Bishop of Prague, and St. Johann von Nepomuk, a 14th-century martyr, contribute to the rich tapestry of Czech Christian heritage.

The Christianization of Hungary, Poland, and Czechia was not merely a religious transformation but also a process that helped shape the emerging national identities of these countries. The veneration of saints like St. Stephen, St. Adalbert, and St. Wenceslas played a crucial role in uniting their respective peoples under a common faith and reinforcing the legitimacy of their rulers. These saints also served as symbols of resistance against external threats, whether from pagan tribes or later, during periods of foreign domination. Their stories and relics became focal points of national pride and sources of inspiration during times of struggle.

Moreover, the shared Christian heritage of Hungary, Poland, and Czechia fostered a sense of cultural and religious kinship among these nations, which has endured through the centuries. The legends and monuments dedicated to these saints are not only reminders of their spiritual contributions but also serve as enduring symbols of the resilience and unity of Central Europe in the face of adversity. These figures and the sites associated with them remain integral to the national narratives of Hungary, Poland, and Czechia, reflecting the deep connections between faith, identity, and history in Central Europe.

Berend, Nora, ed. Christianization and the Rise of Christian Monarchy: Scandinavia, Central Europe and Rus’ c. 900-1200. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Klaniczay, Gábor. Saints of the Christianization Age of Central Europe (Tenth-Eleventh Century). Central European University Press, 2010.

Bagi, Dániel. Divisio Regni: The Territorial Divisions, Power Struggles, and Dynastic Historiography of the Árpáds of 11th- and Early 12th-century Hungary, with Comparative Studies of the Piasts of Poland and the Přemyslids of Bohemia. Institute of History, Research Centre for the Humanities, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 2022.

St. Stephen and others – First christian saints in Hungarian Kingdom – Székesfehérvár

Székesfehérvár, one of Hungary’s oldest cities, holds a special place in the nation’s history as the coronation and burial site of many Hungarian kings, including St. Stephen, the first king of Hungary. This city is a symbol of the foundation of the Hungarian state and the establishment of Christianity in the region. The legacy of St. Stephen and the early saints of the Kingdom of Hungary is deeply intertwined with Székesfehérvár, making it a pivotal location for understanding Hungary’s early history and religious heritage.

St. Adalbert – Gniezno Cathedral

St. Adalbert of Prague, a pivotal figure in the Christianization of Central Europe, holds a revered place in the annals of history. His journey from a Bohemian bishop to a martyr and patron saint of Poland is a tale of faith, diplomacy, and the intricate tapestry of medieval politics. St. Adalbert’s life and legacy are emblematic of the deep spiritual and cultural connections that shaped the kingdoms of Europe, leaving an indelible mark on the religious landscape of the continent.

Patrons of the Czech Lands – Prague Castle – Cathedral

Although the pantheon of Czech patrons includes seventeen figures and cults, only Saint Wenceslas, who has been considered the protector and heavenly advocate of the Czechs, has consistently enjoyed perpetual veneration. The Saint’s feast day, September 28, was commemorated in such spontaneous fashion that the Church had to refute the belief that Saint Wenceslas was the patron of drunkards. The cult of Saint Wenceslas survived the convulsions of the Hussite era and the Reformation unscathed, was cherished by the piety of the Baroque, and the Wenceslas Millenium, an event pragmatically fused with the 10th anniversary of the founding of Czechoslovakia, was opulently commemorated also by the political elite of the First Republic.