For over a thousand years, the history of Central Europe has not been marked simply by a blissful period of peace and prosperity. The nations of Central Europe have also endured periods of collapse, wars or national subjugation.

The events traceable to the beginnings of such difficult times have settled in the historical consciousness of modern Czechs, Hungarians and Poles as fateful episodes. In general, these were “grand” military defeats, from which, in the following decades and in some cases even centuries of national development, stemmed political, social and cultural consequences so significant that they have been regarded as fatal and tragic for further development of a nation and state. Long after having taken place, contemplating these events influenced cultural and political life of the public and formed the desires to reverse or undo the “adverse” consequences.

The myth of a „national catastrophe” constitutes an integral element of the collective imagination of each Central European nation. A comparable „apocalyptic” mythology is associated not only with events from medieval times but also from modern history.

The vast cemetery of our national greatness – The Battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács, fought on August 29, 1526, remains one of the most tragic and defining moments in Hungarian history, often referred to as the „vast cemetery of our national greatness.” This devastating defeat against the Ottoman Empire not only led to the collapse of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary but also marked the beginning of a period of occupation and division that lasted for over 150 years.

„No. No. Never.” – Treaty of Trianon – Monument of National Solidarity – Budapest

The Treaty of Trianon, signed on June 4, 1920, remains one of the most contentious and painful moments in Hungarian history. This treaty, which concluded World War I for Hungary, resulted in the country losing nearly two-thirds of its territory and about one-third of its population. The phrase „No. No. Never.” encapsulates the deep-seated rejection of the treaty by many Hungarians, reflecting the national trauma and enduring sense of injustice that it engendered.

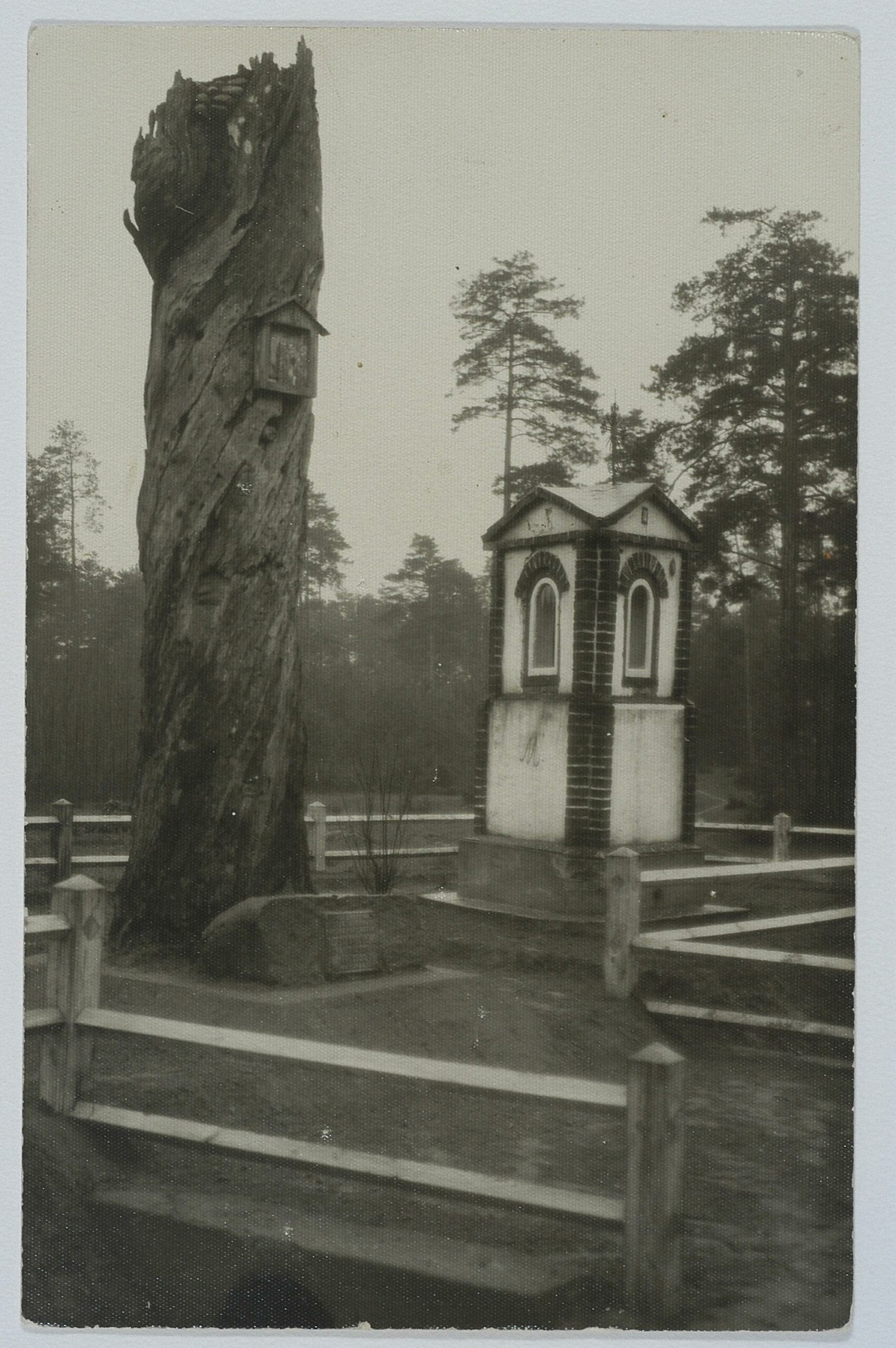

The Battle of Maciejowice – Maciejowice

Internal conflicts among the Polish nobility, excessive concern for maintaining privileges and social inequalities is considered as one of the main reasons for the partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth by the neighbouring Russian Empire, Kingdom of Prussia and Habsburg Monarchy in the second half of the 18th century. Nevertheless, despite animosities, after the second partition it was still possible for the society to unite and organize an uprising – an insurrection, led by the command of General Tadeusz Kościuszko, lasting from March to November 1794.

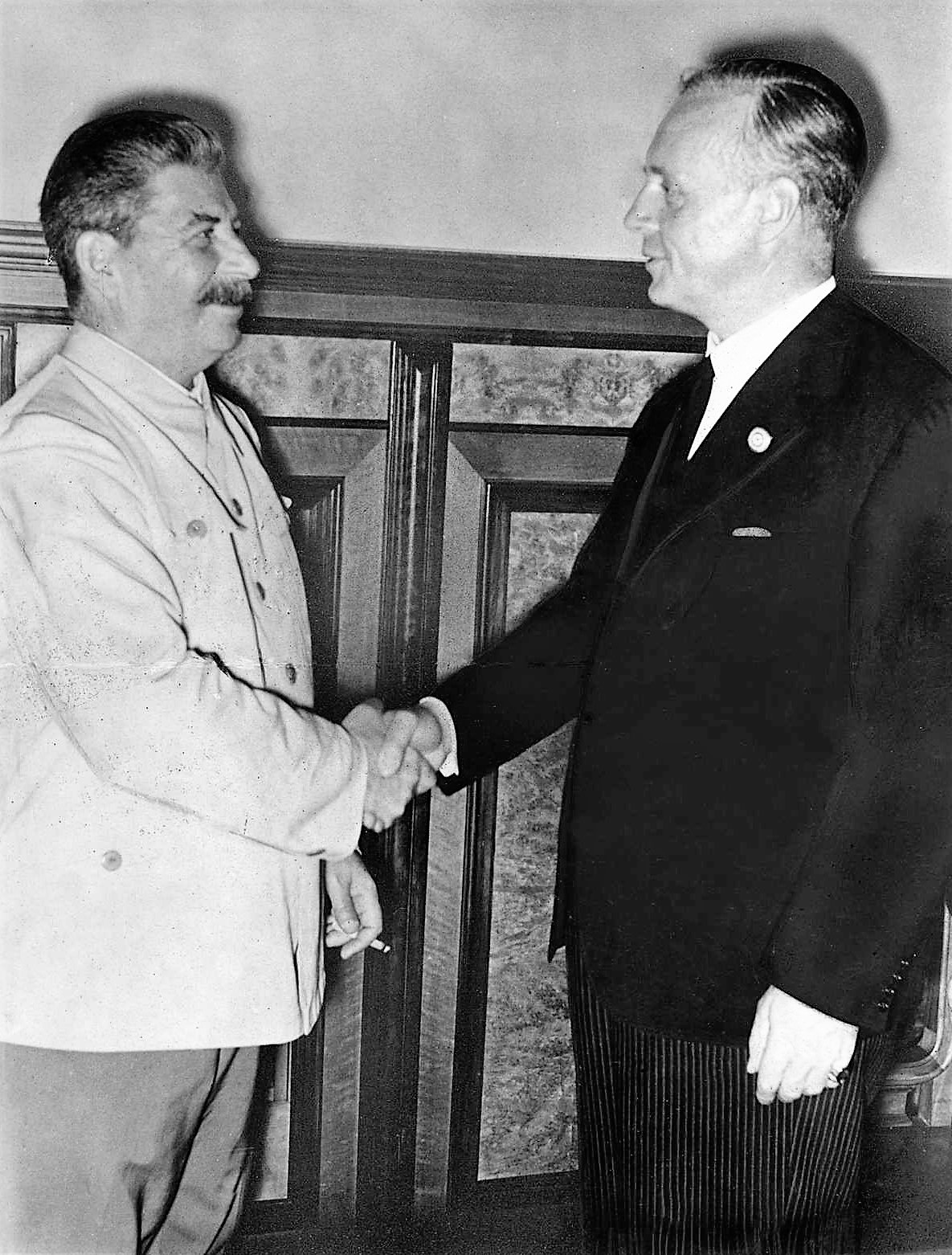

Ribbentrop-Molotov pact – Westerplatte Monument, Gdansk

The Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact, signed on August 23, 1939, stands as a chilling prelude to the devastation of World War II, emblematic of the treachery and political machinations that precipitated the conflict. This treaty between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union was cloaked in secrecy and deceit, setting the stage for the dual invasion of Poland and the subsequent reshaping of Europe under the iron grip of totalitarianism.

The myth of White Mountain defeat – Bílá hora, Prague

The two-hour long skirmish that took place on November 8, 1620, settled within history textbooks as the Battle of White Mountain, assumed an extraordinary place within modern Czech memory. Since the second half of the 19th century, White Mountain has been perceived in Czech culture as a disaster followed by an era of darkness or the prolonged period of decline of the Czech nation, of violent recatholicization and the Germanisation of the Czech lands. Both academic and literary works have ignored that White Mountain did not influence the fate of the nation, but rather the form of governance. The case was whether Bohemia and Moravia would remain a monarchy based on the Estates or whether the influence of Habsburgs reigning from Vienna would prevail and whether the lands would proceed to be bi–confessional: catholic and protestant. Deliberately sidelined was not only the unique Baroque culture which followed but also the fact that, apart from state independence, Czechs, within the Habsburg monarchy, also achieved the political and civil rights monarchy comparable to other European nations.

Munich Agreement – Rokytnice in the Orlické Mountains

The Munich Agreement of 29 September 1938, which saw the European powers cede Czechoslovak territories to Germany, has come to be regarded as the epitome of Czech collective memory of the national catastrophe that occurred in the modern era. As a result of the agreement, Czechoslovakia lost approximately a third of its territory and population, which left the country vulnerable and susceptible to the whims of the Nazi dictator.