World War I shattered the old order in Europe. Vast empires like Austria-Hungary, Tsarist Russia and the German Second Reich crumbled, leaving behind a power vacuum and the yearning for self-determination of the nations. This principle, championed by US President Woodrow Wilson, became a cornerstone for redrawing the map of Europe.

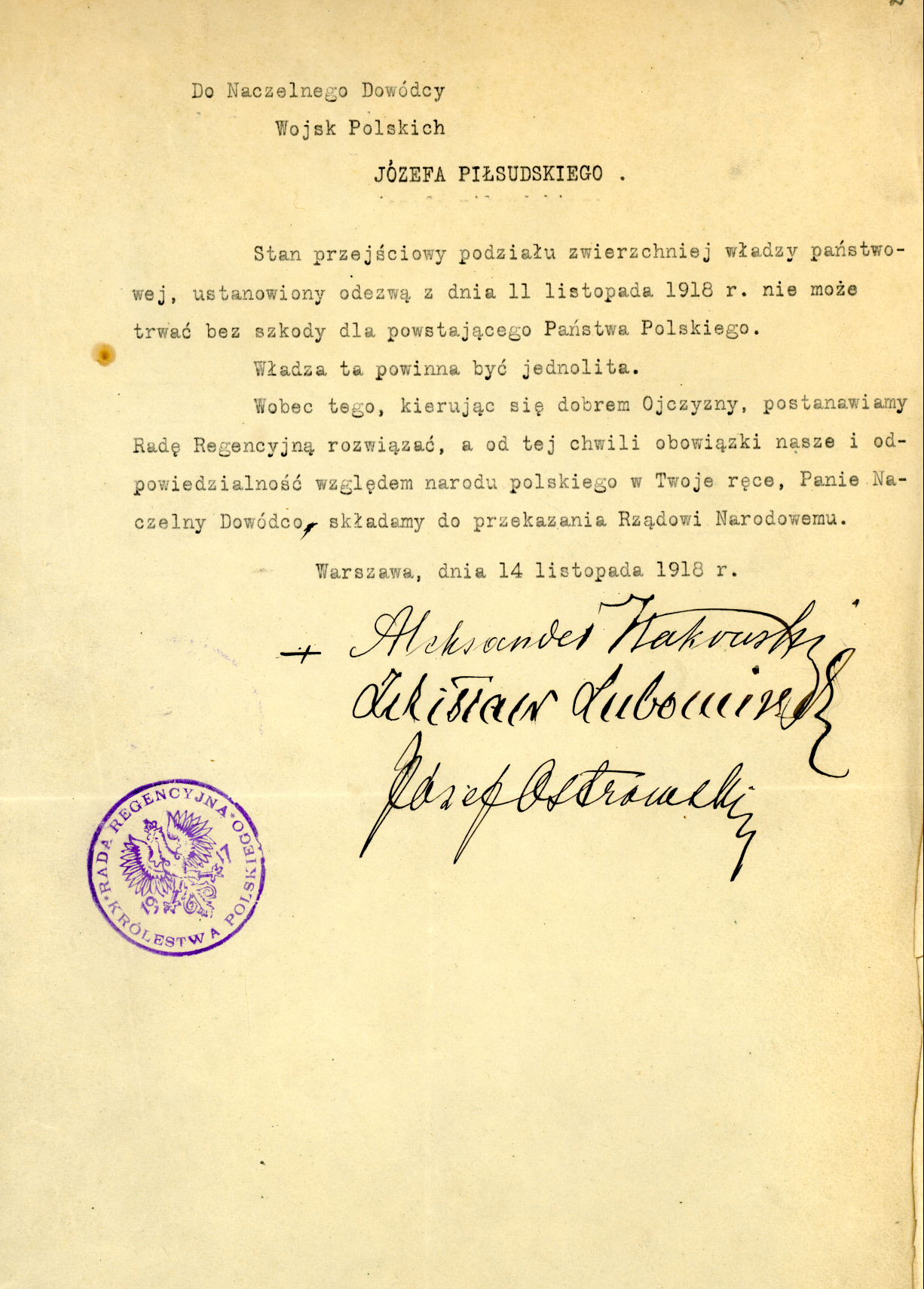

Poland partitioned for over a century seized its chance for freedom. The pivotal moment came with the arrival of Józef Piłsudski, who on November 11, 1918 took control of the Polish Military Organization to assert Polish sovereignty. However, freedom came at a price. The newly formed nation faced a war with the newly established Soviet Union in 1920. This conflict, often seen as a battle for the borders of Europe between the Red Army and the forces of Western civilization, resulted in the miraculous Polish victory at the Battle of Warsaw, often dubbed the „Miracle on the Vistula.”

The post-war scenario was dramatically different for Hungary. The Austro-Hungarian Empire’s disintegration left Hungary in a precarious position. The Treaty of Trianon of 1920 stripped the country of vast territories, creating resentment among Hungarians who felt wronged. The treaty aimed to follow self-determination principles, but it also left significant Hungarian minorities outside the new borders. This fueled tensions with neighboring countries and became a seed of future conflict. Amidst the political chaos, Miklós Horthy, a former Austro-Hungarian admiral, ascended to power as regent, establishing a conservative regime that struggled with economic hardships and social unrest.

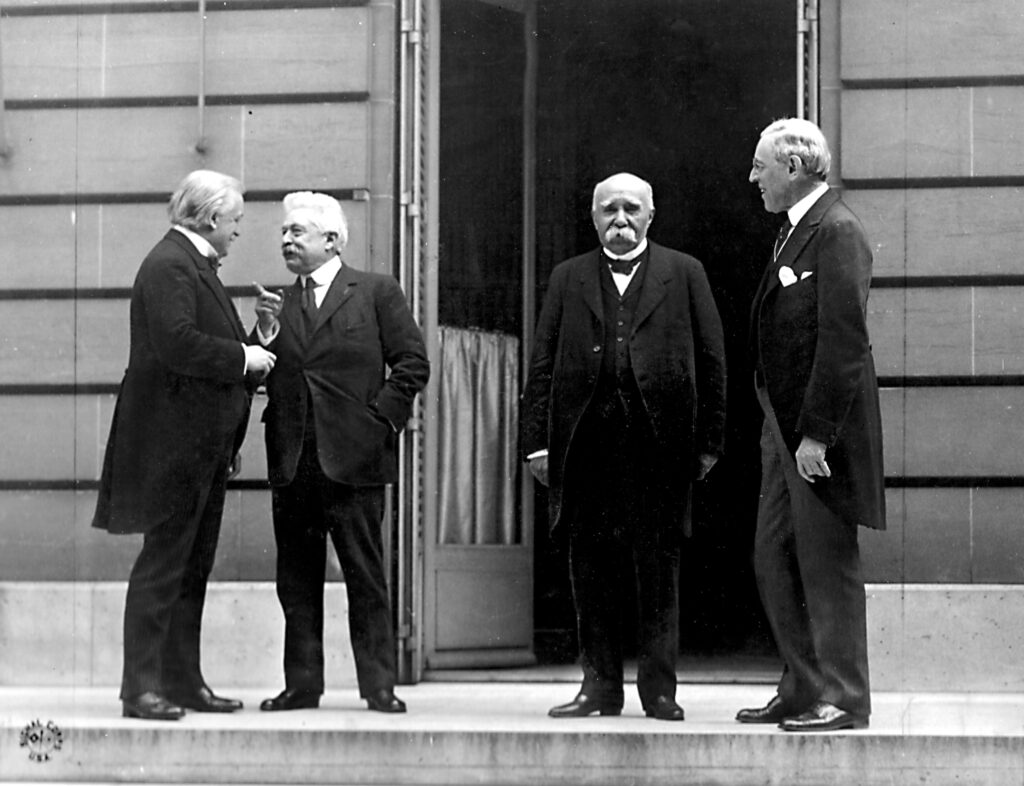

Building on pre-war activism, Tomáš Masaryk, a Czech philosopher and politician, became a key figure in the creation of Czechoslovakia. He advocated for a democratic state that would unite Czechs and Slovaks. The 1918 Declaration of Independence, also called the Washington Declaration, and the subsequent signing of the Treaty of Versailles formalized Czechoslovakia’s existence. Masaryk became the nation’s first president, and under his leadership, the country embarked on a series of reforms aimed at creating a stable democracy. His government implemented far-reaching reforms, including land reforms, extensive social welfare programs, and policies to safeguard minority rights, setting a high standard for democratic governance in the region.

Bibliography

B. Mueggenberg, The Czecho-Slovak Struggle for Independence, 1914-1920, Jefferson 2014.

I. Romsics, The dismantling of historic Hungary: the Peace Treaty of Trianon, 1920, New York 2002.

J. Boehler, Civil war in central Europe, 1918-1921: the reconstruction of Poland, Oxford 2022.

Arrival of Horthy – Budapest, Gellért Hotel

The arrival of Miklós Horthy in Budapest on November 16, 1919, marked a significant turning point in Hungarian history, symbolizing the end of the Hungarian Soviet Republic and the beginning of a new era dominated by Horthy’s regency. Horthy’s rise to power was not an isolated event but the culmination of a series of complex political and military developments that reshaped Hungary in the aftermath of World War I.

The arrival of Piłsudski in Warsaw – Warsaw

As the dust of World War I settled, a historic moment unfolded in Warsaw. On November 10, 1918, a train carrying Józef Piłsudski, the emblematic leader destined to shape Poland’s future, pulled into the city. His arrival was not just a mere return but a pivotal turning point for a nation on the brink of reclaiming its independence. This day marked the beginning of a new chapter in Polish history, as Piłsudski emerged from internment to lead his country out of the shadows of partitions.

“The arrival of Masaryk from war exile to independent Czechoslovakia – České Budějovice

At the beginning of the First World War, the parliament in Austria-Hungary was closed and democratic rights were restricted. As a result of state repression, most Czech politicians were pushed into passivity. Tomáš G. Masaryk went into exile at the end of 1914 and attempted something radically new – he declared a fight for an independent Czech state. The largely hopeless position was reinforced by Czech propaganda in the French and British media. Masaryk was in France joined by the Czech Edvard Beneš and the Slovak Milan Rastislav Štefánik, where they formed an anti-Austrian resistance organisation – the Czechoslovak National Council. Upon his return home four years later in December 1918, Masaryk returned to an independent new state, having already been elected as the first Czechoslovak president.