The Emancipation of Minorities in Central Europe: A Comparative Overview of Hungary, Poland, and Czechia

The emancipation of minorities in Central Europe has been a complex and multifaceted process, deeply intertwined with the region’s tumultuous history, shifting borders, and evolving national identities. Hungary, Poland, and Czechia, with their diverse populations, have each experienced unique challenges and milestones in the struggle for minority rights. From the recognition of ethnic and national minorities to the modern fight for LGBTQ+ rights, the path to equality and inclusion has been long and continues to evolve.

In Hungary, one of the earliest significant efforts to address minority rights was the Nationalities Law of 1868. Passed in the aftermath of the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, this law sought to address the demands of Hungary’s diverse ethnic populations, including Slovaks, Romanians, Serbs, and Germans. While the law recognized the cultural and linguistic rights of these minorities, it also reflected the complexities and limitations of the era, as it struggled to balance the interests of a dominant Magyar nationalism with the aspirations of minority communities.

A century later, Hungary’s commitment to minority rights was further strengthened with the passage of the LXXVII of 1993 law, which laid out comprehensive protections for national and ethnic minorities. This law recognized 13 minority groups, granting them cultural autonomy, the right to use their languages in education and public life, and the ability to establish their own self-governing bodies. It marked a significant step towards integrating minority communities into the fabric of Hungarian society, while also acknowledging the painful legacy of previous assimilation policies.

In Czechia, the issue of minority rights has been deeply influenced by the presence of the German minority, particularly in the Sudetenland. The Act of German language use by Joseph II, which imposed German as the administrative language throughout the Habsburg Empire, serves as a historical example of policies that marginalized Czech and other non-German-speaking communities. The tension between Czechs and Germans culminated in the tragic events of World War II and the post-war expulsions of Germans from Czech lands, leaving a lasting impact on Czech-German relations.

In more recent times, the Czech Republic has taken steps to protect and promote the rights of its minority populations. Museums dedicated to ethnic minorities, such as the German Minority Museum in Ústí nad Labem and the Romani Museum in Brno, serve as important cultural institutions that preserve the history and heritage of these communities. Additionally, the post-1989 era has seen the emergence of new minority groups, including Vietnamese and Ukrainian communities, which have contributed to the multicultural landscape of modern Czechia.

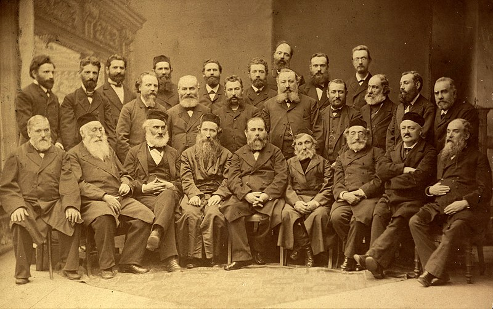

Poland, too, has a complex history of minority relations, particularly with its German and Jewish populations. The birth of Zionism, which emerged in part from the Chibbat Syjon movement, was closely tied to the experiences of Jews in Central and Eastern Europe, including Poland. The Katowice Conference of June 1884, which played a key role in shaping the early Zionist movement, highlighted the aspirations of Jewish communities for self-determination and the challenges they faced in a region marked by rising nationalism and anti-Semitism.

In the context of Polish-German relations, the history of Silesia is particularly significant. The region’s mixed population of Poles, Germans, and Silesians (Schlonzaks) has led to a complex interplay of identities and loyalties, especially during the turbulent 20th century. The post-war expulsion of Germans and the resettlement of Poles in former German territories reflect the broader patterns of population displacement and forced migration that have shaped Central European history.

Cultural memory plays a crucial role in the emancipation of minorities in Central Europe. Museums dedicated to minority histories, such as the Polish Museum in Český Těšín (Czechia) and Roma Memorials in Hungary, serve as vital spaces for preserving and promoting the cultural heritage of these communities. They also provide a platform for dialogue and education, helping to bridge the gaps between majority and minority populations and fostering greater understanding and empathy.

Theodor Herzl, often regarded as the father of modern Zionism, is another figure whose legacy continues to influence discussions about minority rights in Central Europe. Born in Budapest, Herzl’s vision for a Jewish homeland was shaped by his experiences in a region marked by ethnic diversity and rising nationalism. Herzl’s work, including the founding of the World Zionist Organization, laid the groundwork for the eventual establishment of the State of Israel and has had a lasting impact on Jewish communities worldwide.

Minorities in Hungary – Tata

Tata, a picturesque town in Hungary, is not only known for its historical and natural beauty but also for its role in the broader narrative of minority rights within Hungary. The town is home to the German Minority Museum, which serves as a testament to the presence and contributions of ethnic minorities in Hungary, particularly the German community, also known as the Danube Swabians. The museum in Tata offers a lens through which we can explore the broader issue of minority rights and the emancipation of minorities in Hungary and Central Europe.

The birth of Zionism – Chibbat Syjon – Katowice

Chovaev Zion, or ‘Lovers of Zion’, was a Zionist movement established in the late 19th century in Eastern European lands. It focused on promoting Jewish emigration to Palestine and supporting settlement in the territories. The movement originated as a reaction to anti-Semitism and pogroms in Tsarist Russia. Along with other Zionist organisations, Chovevei Zion played an important role in the formation of Jewish identity and the push for a Jewish state.

The difficult search for multiethnic coexistence – Ústí nad Labem

The contemporary Czechia is constituted by three historical regions: Bohemia, Moravia and a portion of Silesia. The territory has been inhabited for millennia by a multitude of ethnic groups. In ancient times, the area was inhabited by the Celts, the first known inhabitants of the Czech lands. During the Roman Empire, it was populated by the Germans. The Boii, one of the Celtic tribes that inhabited the territory, bestowed upon it the name Bohemia in Latin and numerous other foreign languages. Following the departure of the Germanic Marcomanni during the Migration of Nations, the region was populated by Slavic tribes, among whom the Czechs established a dominant presence.